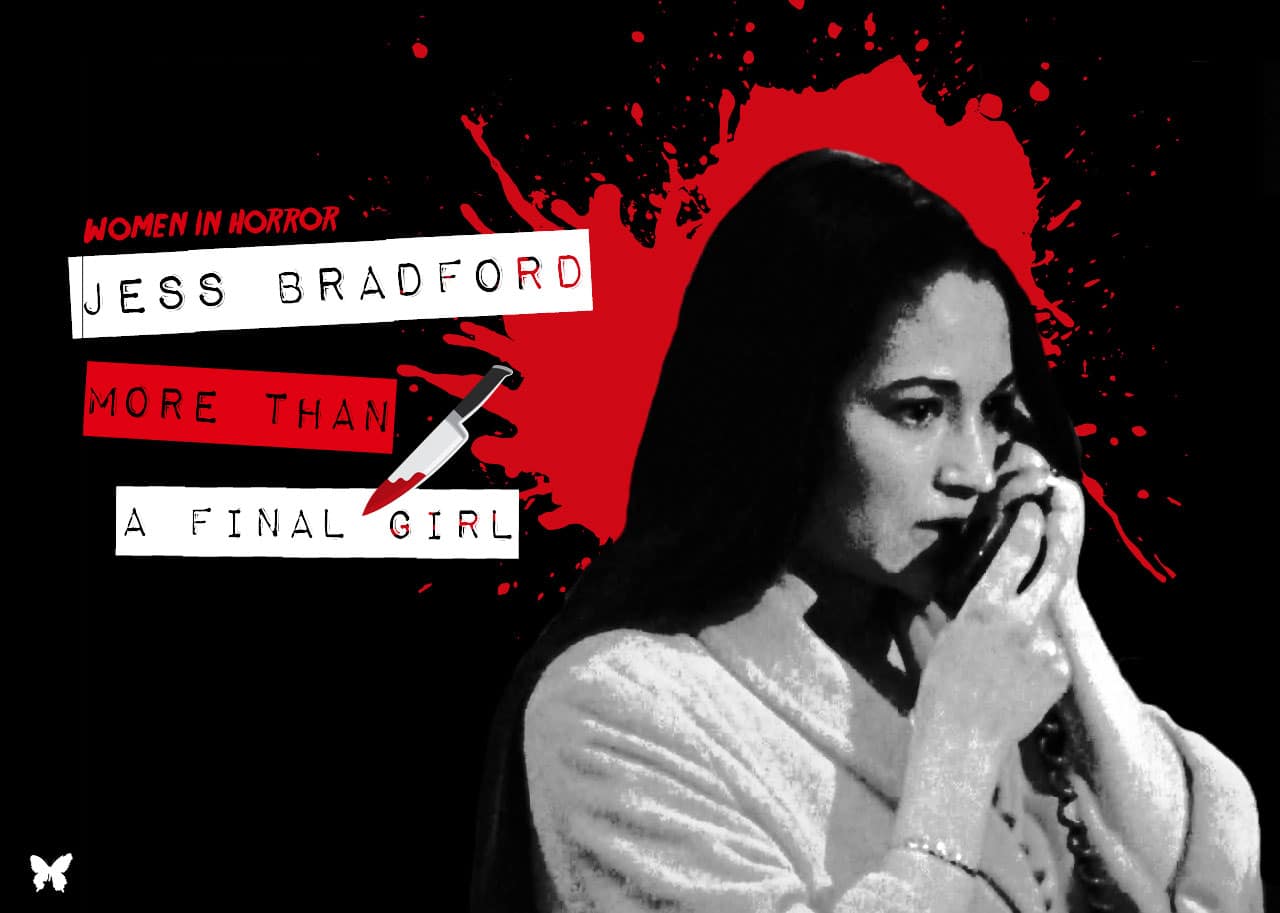

As we celebrate one of the greatest Christmas horror films of all time, we recognize the unsung legacy of the ultimate final girl, Jess Bradford.

In her 1992 book Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, Carol Clover coined the term Final Girl and refers to Halloween’s Laurie Strode as “the original Final Girl.” Nearly two decades later, Laurie is still widely regarded as the OG, just as Halloween is widely regarded as the first slasher film. But while John Carpenter’s 1978 film was certainly the first to bring the slasher into the mainstream consciousness, Halloween was not the first of its kind.

This subgenre has roots in Italian giallo, Psycho, Peeping Tom, and others, but the modern slasher as we know it — the familiar formula that’s still going strong today — was born in 1974 with Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Bob Clark’s Black Christmas.

If you want to split hairs, TCM predates Clark’s film by two months, which means Sally Hardesty is technically the first Final Girl. But I’d argue that Black Christmas is the film that most embodies the slasher, due in no small part to its major, obvious influence John Carpenter and Halloween.

So why does Laurie get all the credit when Black Christmas’ Jess Bradford is literally right there?

This isn’t to knock Laurie or to attempt to deny the importance of her role or her film. Pitting Final Girls against each other is pointless, because they are all amazing, tough as nails survivors who should be celebrated. My question is simply: why isn’t Jess as widely celebrated as her sisters like Laurie, Sally, Nancy, and Sidney?

The fact that Black Christmas is a Canadian film probably has a lot to do with it. Horror film discourse (and film discourse in general) has a definite American bias. Even Carol Clover focused almost exclusively on American films in her book, explaining why Black Christmas and Jess are tragically omitted from her analysis.

Jess both embodies and transcends Clover’s framework for the Final Girl. She’s a shockingly radical character for her time — or any time — and while her journey is one shared by all Final Girls, she can’t be quite so easily boxed in by some of the familiar tropes.

The first indicator of a Final Girl, according to Clover, is that the character is established at the beginning of the film as the main character, the only one among the cast to be “developed in any psychological detail.” Clover describes her as “intelligent, watchful, level-headed,” and “resourceful in a pinch.” She is the last character standing, “the one who looks death in the face,” and confronts the killer rather than fall victim to him.

Jess is established as the heart of Black Christmas in the first five minutes of the film.

We’re drawn into her story immediately, when we overhear her on the phone with her boyfriend Peter. It’s clear something is troubling her, and that conflict plays a pivotal role in her narrative, as well as the overall narrative.

Her sorority sisters Phyl, Barb, and Claire are drawn with less detail — enough to give them individual, distinct personalities, but not so much that we forget that the story belongs to Jess.

Jess’ level-headedness and maturity is highlighted mostly in contrast to Peter, a deliberate reversal of horror’s standard of hysterical women and men who keep telling them to calm down. We get the sense that Peter has always been manipulative and controlling, and he only becomes more so after Jess announces that she’s pregnant and plans to have an abortion. He is emotionally volatile throughout the film, while Jess repeatedly pleads with him to have a “rational, adult conversation.”

Even among her sorority sisters, Jess is a rock.

While Phyl and Barb react in their own ways to Claire’s disappearance, Jess somehow manages to hold it together up until the end. Her inner turmoil is clear, but her practicality and sense of responsibility is what sets her apart from her friends (and her boyfriend).

It’s this sense of responsibility that drives her to “look death in the face,” to come face to face with the killer.

The girl who runs upstairs instead of out of the front door has long since become a running joke in slashers, but Jess originated the trope — and it’s a testament to her strength. Instead of running away when she learns that the killer is inside the sorority house, she clings to the slightest hope that Phyl and Barb might still be alive and refuses to leave without them, arming herself with a fireplace poker and heading upstairs to find her friends.

The fireplace poker, of course, is the obligatory phallic symbol that the Final Girl carries into the final showdown. With the poker, knife, chainsaw, or whatever other pointy object, the Final Girl “unmans” the murderer, taking away his power by symbolically castrating him.

What makes Black Christmas unique is that Jess doesn’t actually kill the killer.

The film sets up her abusive boyfriend Peter as a red herring, and it isn’t until the final scene — after Jess has killed Peter in self defense, believing him to be the murderer — that we learn that the real killer is still alive and in the attic, his identity unrevealed. The line separating Peter from the deranged murderer is blurry at best; the fact that they aren’t all that different is perhaps the point the film is trying to make. At any rate, by killing Peter, Jess fulfills her Final Girl destiny of “unman[ning] an oppressor,” freeing herself from his abuse and the life he wanted to force her into.

There is, however, one tenet of the Final Girl framework that Jess flagrantly defies.

According to Clover, one of the most important aspects of the Final Girl — what gives her a purported moral superiority and allows her to triumph where others cannot — is the fact that she is not sexually active. This usually puts her in stark contrast with the other women in the film, whose sexuality marks them for destruction at the hands of the killer. The small handful of Final Girls who are explicitly non-virginal (Clover’s examples are Stretch in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 and Stevie in The Fog) are usually “unattached and lonely” women who “decline male attention.”

Jess falls somewhere else entirely on this spectrum.

The major component of her narrative — being a sexually active unmarried young woman who plans to terminate an unwanted pregnancy — puts her in closer proximity to the characters that Clover refers to as “sexual transgressors,” characters like Psycho’s Marion Crane, whose improper sexual behavior is swiftly and violently punished.

In any other slasher, Jess is exactly the kind of girl who would be killed first.

(Think of Hello Mary Lou: Prom Night II’s appropriately named Jess, another young woman with an unplanned pregnancy, who is the first victim of Mary Lou’s vengeful spirit.)

Yet unlike most of the characters who fall into the “sexual transgressor” category — Halloween’s Lynda, Nightmare on Elm Street’s Tina, or basically any sexually active teenage girl or young, unmarried woman in any slasher film — Jess’ sexuality isn’t overt. Sex isn’t her main prerogative. Her general demeanor aligns her more closely with the quiet, virginal Laurie Strode, though Black Christmas rejects the notion of moral superiority that Halloween assigns to Laurie for her abstinence.

Perhaps the Final Girl that most resembles Jess is SCREAM’s Sidney Prescott. Wes Craven’s 1996 film has been praised for subverting slasher tradition by allowing its Final Girl to lose her virginity and still survive. It took over two decades for another Final Girl to break the mold that Halloween solidified in slasher canon.

Jess broke the mold before it was even made, which is why her absence from Clover’s analysis and subsequent scholarship on the slasher film is so confusing and frustrating.

Clover credits slashers of the 1980s with creating a Final Girl who saves herself. The Final Girls of the 1970s — The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’s Sally and Halloween’s Laurie — are both rescued by a “last minute male,” who either whisks her to safety (Sally) or takes down the killer for her (Laurie). Again, this completely ignores the existence of Black Christmas and Jess, without whom the “active defense” of 80s slashers probably wouldn’t exist.

Most horror fans know their history and recognize the importance of Black Christmas as one of the most influential early slashers. But to casual viewers and in our collective consciousness, it still too often gets obscured by Halloween’s long shadow.

Fortunately, there are plenty of folks out there championing the film’s rightful place in horror history, carrying on its radical legacy (see: Sophia Takal’s 2019 reboot), and giving credit where credit is due: to the extraordinary character who both defined and defied the Final Girl archetype.

Jess Bradford walked so other Final Girls could run (up the stairs, of course).

Follow Us!