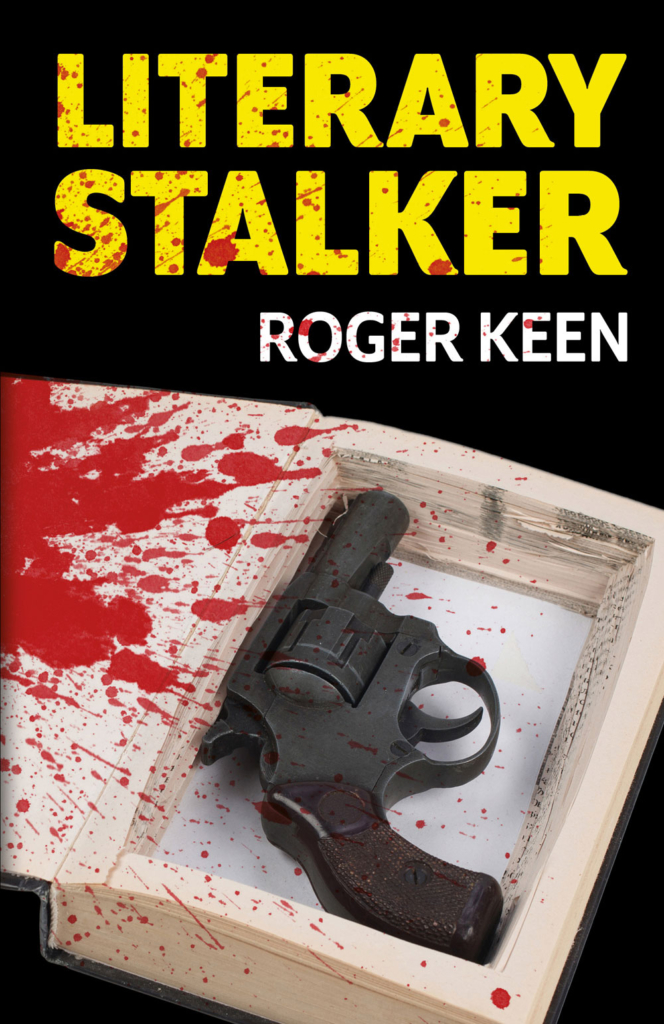

The Real Life Stalkers That Terrorized Your Favorite Horror Authors and Inspired Some Great Fiction, Including the New Novel “Literary Stalker”.

Editor’s Note: We are so fortunate to have this special guest post from talented author Roger Keen, who really impressed us with his recent horror fiction novel Literary Stalker (reviewed here on this site).

My novel Literary Stalker constructs a fictional scenario where a writer/fan becomes embittered by a series of negative encounters with others in the writing game, and in one particular case he tips over into becoming a stalker, heading inexorably towards bloody revenge.

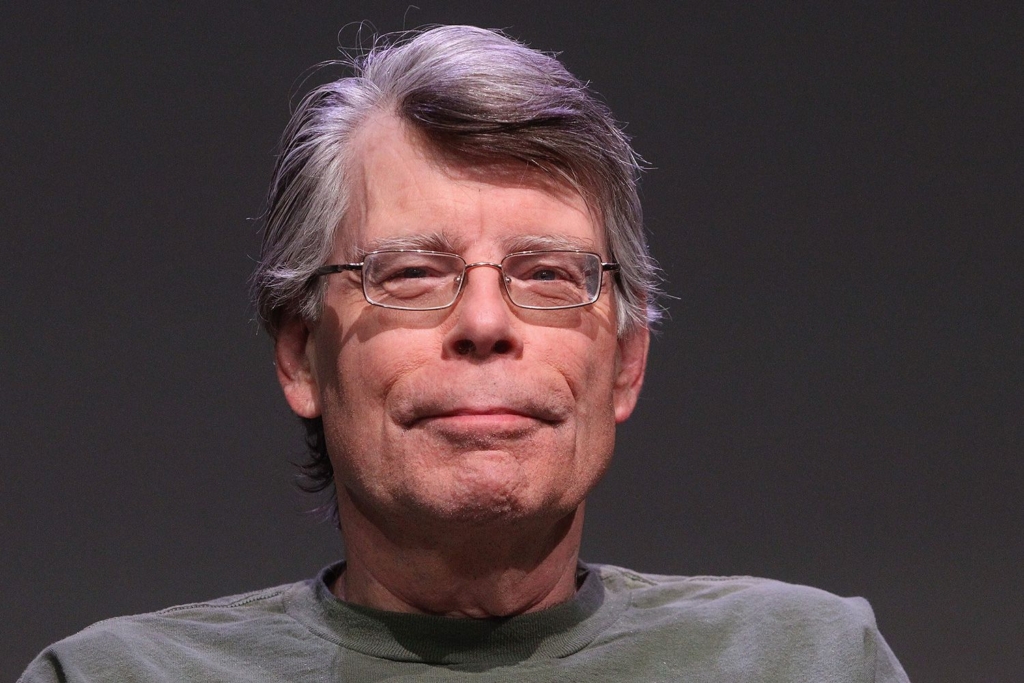

In fiction, a variation on this theme has been explored most famously by Stephen King, who gave us literary stalker Annie Wilkes in Misery, and brought to life every paranoid writer’s worst nightmare. But what about in real life? Are there actual literary stalkers out there, preying on illustrious scribes? You bet there are!

Ironically Stephen King once thought that by writing about bad things you prevented them from happening in reality, and this provided a basis for his horror fiction. One would think, then, with Misery under his belt, he was well ‘insured’ against literary stalkers! But think again…

In April 1991 – four years after the publication of Misery and just five months after the release of the film – King’s wife Tabitha was home alone at their mansion in Bangor, Maine, when she heard the sound of breaking glass coming from the kitchen. Trying to escape, she encountered Erik Keene, who claimed to have a bomb in his rucksack. Tabitha managed to flee to a neighbor’s house and the police were called. After sealing off the street and using a sniffer dog, they found Keene in the attic with some calculator parts, put together to resemble a bomb, and he was arrested on charges of burglary and terrorizing.

Two days previously, Keene had visited Stephen King’s business office, telling an assistant, Shirley Sonderegger, that Misery was his literary property, based on the life of his aunt, and he wanted room and board whilst collaborating with King on a sequel. When told this wasn’t possible, he became angry and stormed out.

It turned out that Keene was a big King fan – and also a schizophrenic on parole in Texas. Though he entered an insanity plea at his trial, he was convicted and served four months, before being extradited back to Texas. He promised to bring King a present ‘from the macabre’, which he said his grandmother had given him before she died.

So, far from insulating King from the problem of wacko stalkers, Misery had attracted them. The following year, another turned up in Bangor, also suffering from delusional beliefs. By means of coded messages, Steven Lightfoot had discovered that King had killed John Lennon, and the actual murderer, Mark David Chapman, was a mere decoy, an actor in a hoax.

Lightfoot parked a van in downtown Bangor which was festooned with messages and a web link concerning King’s crime, and he was eventually served with a protection-from-harassment order. Then, in 2003, Bretislav Bures, an illegal immigrant from the Czech Republic, was arrested for stalking after approaching Tabitha and leaving crazy notes in the Kings’ mailbox, and demanding to speak to the writer. King was fearful enough to load his handgun, just in case. And in 2013 another trespass took place at the King home, resulting in a struggle with police and an arrest.

As a high profile author who deals in obsession and the macabre, it’s somehow not surprising that Stephen King has been targeted by nut-job fans, and those cases all took place at his mansion, which itself is a magnet as a kind of Victorian Gothic edifice to himself and what he stands for.

In Literary Stalker, obsessed fan Nick targets famous British horror writer Hugh Canford-Eversleigh at both his posh London home in Edgerton Crescent and his country estate in the Cotswolds, but Nick also takes advantage of that classic interface – and point of vulnerability – between reader and writer: the book-signing session. And in this particular area several real writers have had problems with stalkers too.

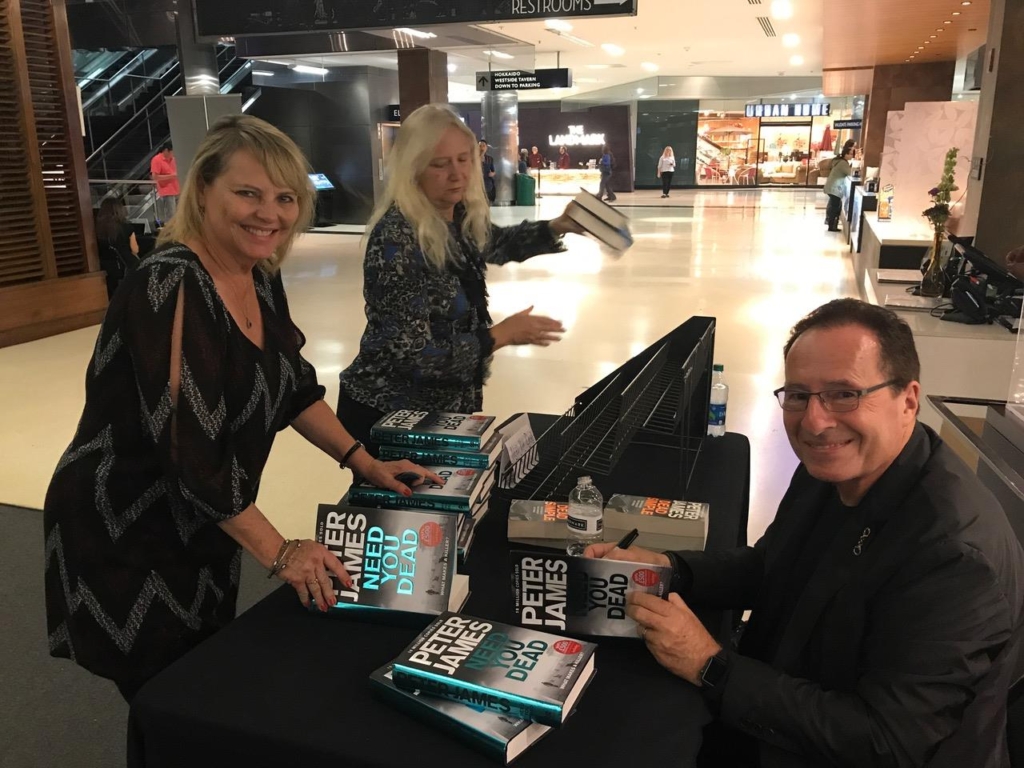

Whilst on a book tour of Britain, crime writer Peter James became aware of something untoward. In Edinburgh he signed a book for a smiling female fan, and he thought no more about it – until he spied her in the audience a week later in Norwich, and again the following week in Cardiff. With considerable knowledge of celebrity stalkers from his work in movies, James now faced the situation of having one of his own, but he tried not to let it bother him…not at first.

Soon he was inundated with emails from this woman, which became progressively longer, more intimate and more demanding. Her attendances at signings and messaging went on for years, and her attitude was that a ‘special relationship’ existed between James and herself – a classic symptom of obsessive love or erotomania. James himself learned to live with it, but inevitably the situation began to get darker and more potentially dangerous.

She sent photographs of her ‘Peter James collection’, consisting of a wall of his books, plus framed author photographs and photos she’d taken herself, flanked by candlesticks so that it resembled a shrine. From her own photos, it was clear she’d been stalking James, following him around and capturing his daily routines. Her emails became more obsessive, and one day a scented letter arrived, filled with declarations of love.

James, haunted by thoughts of Misery – not to mention Fatal Attraction! – increased security at his home, but it didn’t prevent a break-in (the perpetrator was never traced). And still the stalker continued to turn up at signings, and one time she castigated James for failing to recognize her…but then at a subsequent encounter she said, smiling, that she’d forgiven him!

Indeed, the interface of the signing event is an unavoidable potential flashpoint for high profile writers who must meet the public and sell their wares as part of their professional commitments. Nick in Literary Stalker knows this only too well, and he taunts Hugh Canford-Eversleigh with suggestions of impending peril, and attends Hugh’s signings with murder in mind.

Another crime writer, Val McDermid, had a nasty experience at a signing when Sandra Botham turned up disguised in a wig, hat and glasses, and asked McDermid to sign a copy of her non-fiction book A Suitable Job for a Woman. Botham then threw ink all over McDermid, the reason being the former held a grudge against the latter because she interpreted a description in the book as a slight against herself – a woman called ‘Sandra’ was said to be shaped ‘like a Michelin Man’.

Scottish writer Janice Galloway reports an incident where a man queued for over an hour at a signing, only to tell her he hated her writing, and her ‘fucking earrings as well’! Galloway also had trouble with a mentally unstable ex-partner stalking her, requiring several court visits before obtaining an order banning him from contact.

Ian McEwan, who wrote the stalker novel Enduring Love, has said he fears being shot at book signings – particularly in the USA where guns abound – and he’s constantly scanning his audiences for dodgy-looking punters when on book tours. McEwan has also had ex-wife problems, which came to a head at the Cheltenham Literary Festival in 2014, when he was giving a talk followed by a signing.

Penny Allen used the opportunity to heckle McEwan over their acrimonious divorce and child custody battle, and in particular the injunction he had placed on her, forbidding her from talking about the case. She was especially enraged because McEwan had been mentioning their legal battle in promoting his then current book, The Children Act, whilst she was gagged in that respect.

So when it comes to book signings, authors beware! But away from the coal face of public encounters, other stalking problems lurk.

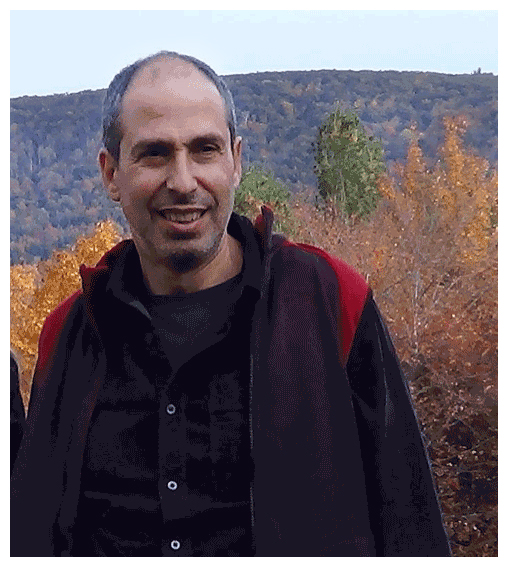

James Lasdun formed a friendly platonic relationship with a former student and aspiring novelist whom he calls ‘Nasreen’, conducted mainly by email, but after her messages became flirty and he failed to adequately reciprocate, the whole thing tipped and Nasreen turned accusatory and abusive.

This escalated into an online campaign where she alleged sexual misconduct and plagiarism, posting on Amazon, Goodreads, Facebook and altering Lasdun’s Wikipedia entry. She was quite ingenious and even ‘creative’ in her attacks, mixing up Lasdun’s fiction, so-called facts and her own projections into a garbled info-salad. She describes herself as a ‘verbal terrorist’.

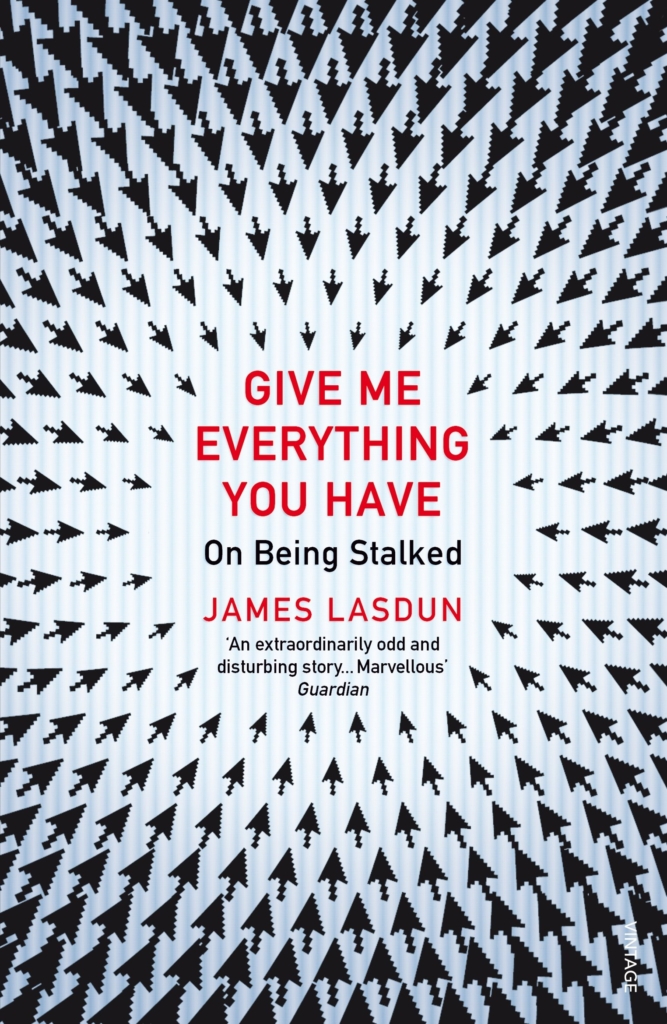

Here I give only a perfunctory outline of a very complicated affair, and Lasdun himself has told the extended story in a stalking memoir: Give Me Everything You Have. It is a most interesting case, blending literary elements and social media propensities with more traditional stalking bitterness in a very left-field way.

What can we learn, then, from specifically literary staking cases as opposed to the more general kind?

As with classic celebrity stalking, writers can be targeted by starstruck obsessed fans, but such fans are also readers and may well be critics and deranged theorists into the bargain. Stalkers may believe they have had their ideas stolen by the writer – as with Erik Keene and Stephen King’s Misery – or they may accuse the writer of plagiarism in order to besmirch a reputation – as with Nasreen and James Lasdun.

An obsessed mindset might detect messages, signals or threats within a writer’s text itself, and act on them – as with Sandra Botham and Val McDermid’s perceived slur. Whatever the trigger, the formal set-up of the book-signing event figures as highly suitable for a gunslinger-style showdown, and touring writers may find themselves on the receiving end of a hissy fit (Peter James), critical invective (Janice Galloway), a face full of ink (Val McDermid), or the continuation of a marital row (Ian McEwan).

But perhaps differently from other celebrity victims, stalked writers have special opportunities for redress.

They can mould their stalking stories into publicity tools, or even assemble an entire memoir, as in James Lasdun’s case. And stalkers don’t usually get a ‘right of reply’. Fiction writers can turn the tables on their tormentors by using them as models for unsympathetic characters in novels – as Peter James did in his hair-raising Roy Grace thriller Not Dead Yet. In the same book, James also settles a score with literary doyen Martin Amis, creating the character ‘Amis Smallbone’, a down-at-heel old gangster – no prizes for guessing what anatomical deficiency he suffers from with that surname!

My novel Literary Stalker ticks many of these boxes. As well as feeling under-appreciated by his love object, Nick also believes that Hugh Canford-Eversleigh has stolen his ideas and is a plagiarist generally. What’s more, Nick perceives many disparagements of himself within the text of Hugh’s work, which may well be retaliation for his stalking – everything is seen from his own warped unreliable perspective.

Ultimately, in desiring revenge Nick sights the book-signing event as the ideal venue for an apocalyptic confrontation. He is determined to have his ‘right of reply’ to Hugh’s various mistreatments of him, and inevitably he pushes it far too far…Will this ever happen in real life? We shall see.

2 Comments

2 Records