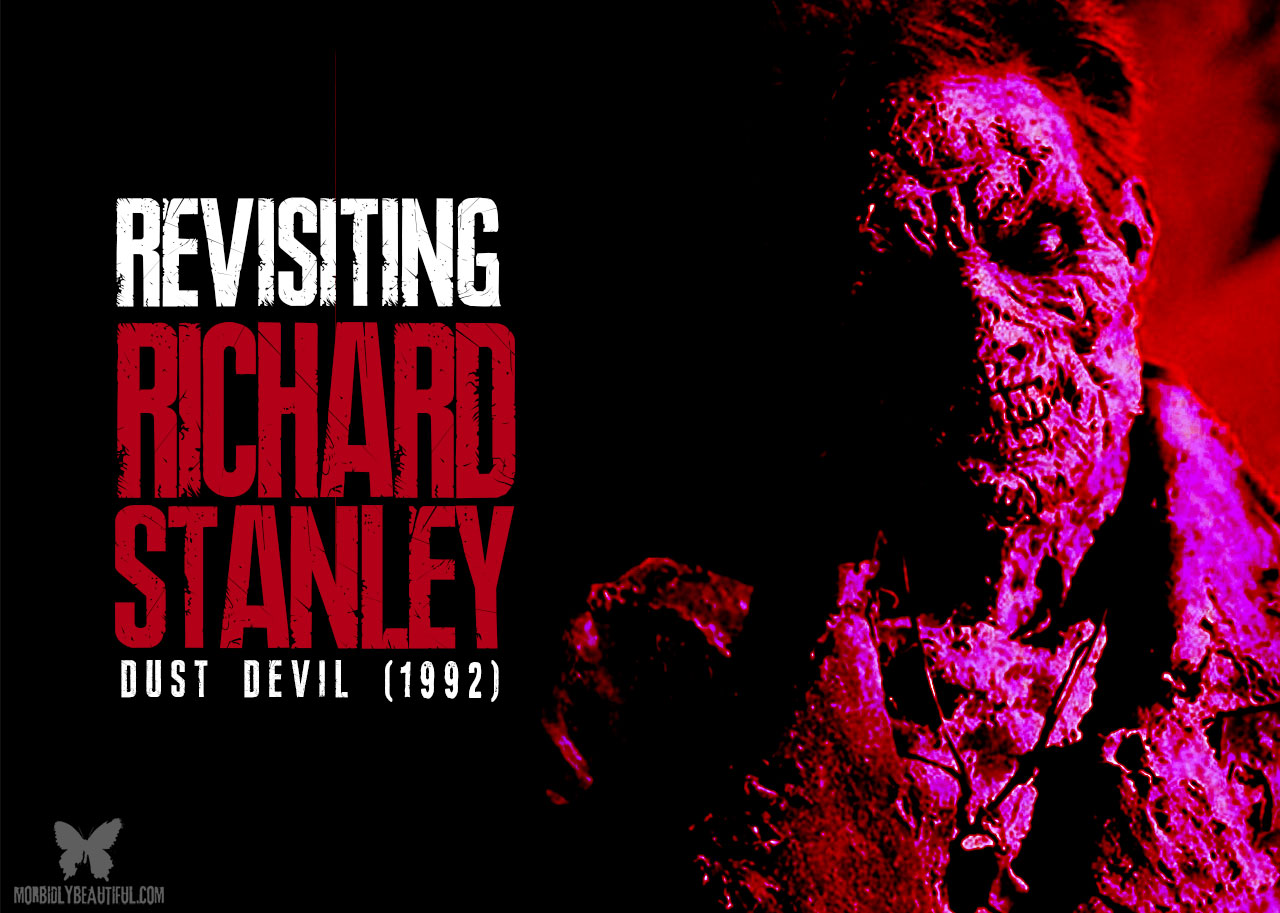

We continue our retrospective of Richard Stanley’s career with a discussion of his psychedelic spaghetti western slasher film “Dust Devil” (1992).

“I was brought up by a strong mother who was involved in witchcraft,” Richard Stanley says, reflecting on his upbringing.

This association to ritual and magic is no surprise. His uncanny films transfix viewers with their unique, uncompromising vision. Stanley’s first film, Hardware (which we talk about in depth here), took viewers to a haunting nuclear future and begged deep questions about humanity’s relationship with intelligent machines. The film rippled through the genre film community and launched the young director’s career.

More importantly, Stanley proved that he could create a motion picture suited to mainstream audiences. As soon as Hardware hit theaters, genre fans looked to Stanley as the next big thing in horror and wondered where he would go next. It’s no surprise that he ventured into something far stranger than his first film.

In a sharp turn, Stanley chose a project that is intimately tied to his past.

He abandoned robotics, dystopian futures, and nuclear fallout for a movie that is equally as visual as Hardware, but far less inspired by science fiction. A native South African, he crafted a story of unsolved murder and, more importantly, developed a narrative about a harshly divided cultural climate.

But Stanley had far more than a slasher film up his sleeve.

Along with setting and story from South Africa, witchcraft, magic, and myth factor heavily into Stanley’s second feature, Dust Devil.

This intimate and symbolically rich sophomore effort does not disappoint.

Dust Devil is hallucinogenic spaghetti western, a ritualistic tale of myth and legend, and a slasher film that does not fear facing the cultural ramifications of apartheid governance. In short, Stanley’s second film is a symbolically dense examination of Namibia’s history, without ignoring the fundamental damage of racial segregation.

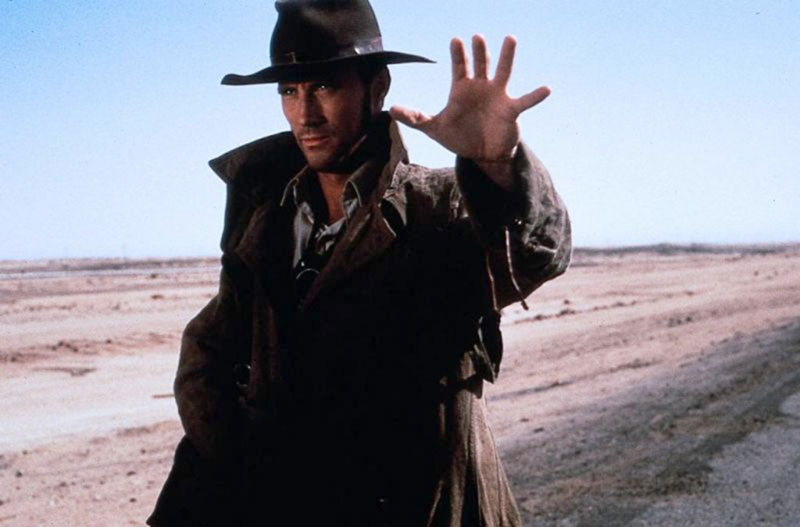

Dust Devil explores a group of disparate narratives that are fated to come together. A dark magician (Robert John Burke) who feeds off of hopeless people looks for his next victim to fulfill his need for ritual slaughter. Wendy (Chelsea Field) runs from an abusive relationship, determined to see the ocean and to find a new life. Following their trail, Ben Mukurob (Zakes Mokae) struggles with his service to a government and country that does not want him. The three are destined to collide and they won’t all make it out alive.

Unlike Hardware, Stanley blends together multiple storylines into an experimental and horrifying narrative. The film is frenetic, jumping from character to character. However, the plot does not stop Stanley from creating visually striking cinematography that harkens back to the desert landscapes of Hardware.

But Dust Devil goes far beyond beautiful imagery by centering a character who is intimately tied to apartheid.

Ben Mukurob is described as a man “…grown tired from serving a country that didn’t want him. Chasing mirages in the dust.” A cop stuck in a dying town, Mukurob, it seems, is Stanley’s grizzled, hardboiled detective. He is old, full of guilt, and hopeless. Through his horrific, hallucinogenic dreams we learn about his torrid history and his inability to recover from the past. Yet, he is the film’s most important character.

His ties to myth and magic, despite his skepticism, make him the only one able to understand the Dust Devil. With Mukurob, Stanley speaks about the importance of myth and preserving ancient practices over commonly accepted modern thought.

Mukurob, as a black man, also signals the importance of racial tensions in country still in the midst of racial segregation. By interweaving these ideas of cultural and race into the film, Stanley showcases the larger political implications of South Africa as a setting and proves his ability to include a genre film into a wider political conversation.

Beyond its innovative location and political implications, Dust Devil’s titular character is both terrifying and intriguing.

Robert John Burke’s performance as the Dust Devil is laudable. He manages to be menacing, terrifying, sexy, and enticing. He’s not the normal slasher. His chameleon-like abilities entrance the audience, which makes his hyper-violence all the more terrifying.

Between his bodily transformation, his multiple curved knives, and his predilection toward drawing symbols in human blood, the Dust Devil manages to be a nightmare-inducing antagonist that makes us think twice before driving through the desert.

Yes, Dust Devil has flaws. There are pieces of dialogue that don’t always work, some of the characters are one-dimensional, and, at times, the narrative can be heavy handed.

However, Stanley’s second feature film is a gamechanger.

It tackles myth, history, politics, and horror with aplomb and continues Stanley’s ascendance as a director with a natural talent for capturing beauty in devastation.

Like the Dust Devil, Richard Stanley does not stop moving. His next project proves to be his most ambitious and his most disastrous. It’s a story that Stanley deeply values.

Unfortunately for the young director, his passion project will lead him to near ruin and an over 20-year estrangement from the director’s chair.

Next month on Revisiting Richard Stanley, The Island of Dr. Moreau.

Follow Us!