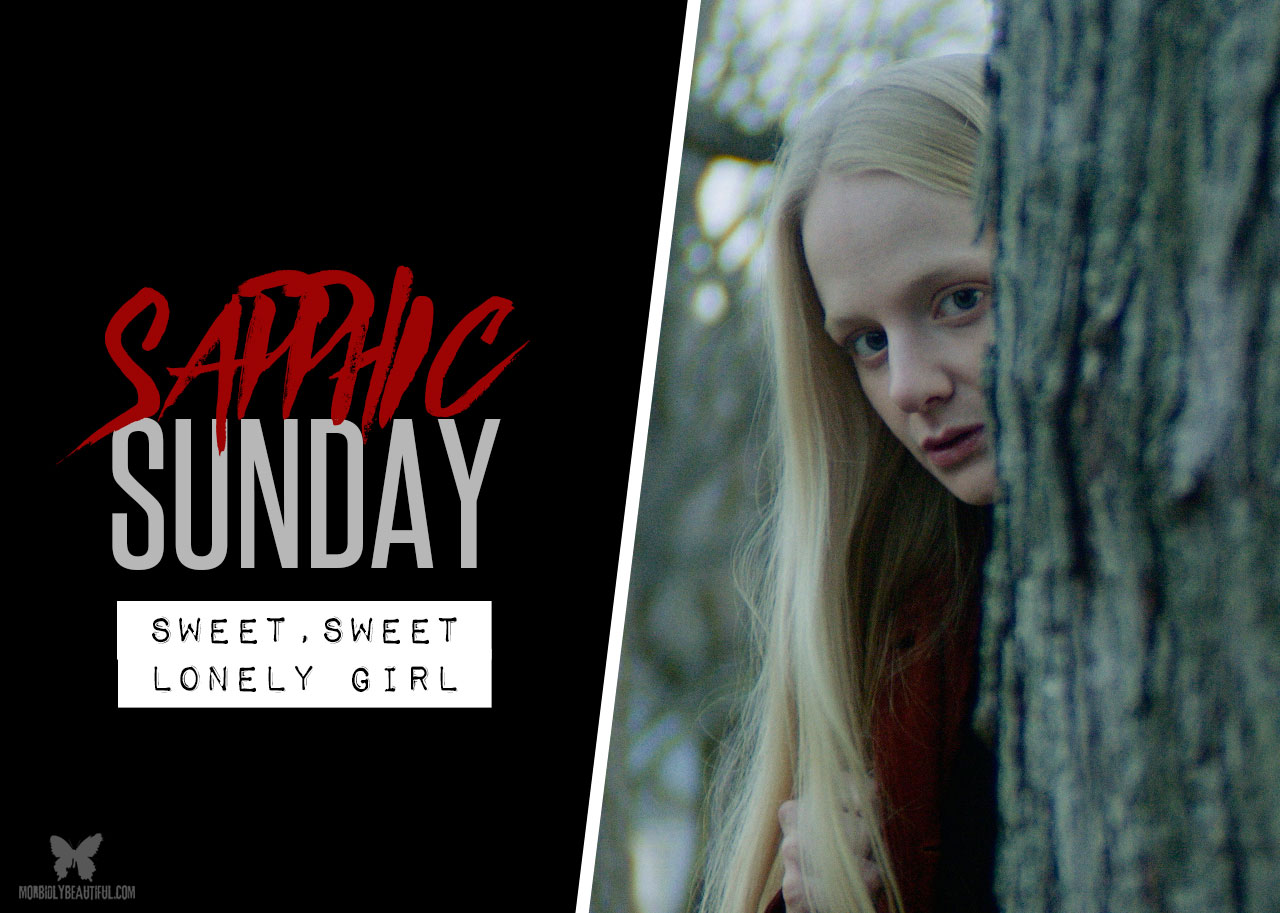

“SWEET, SWEET LONELY GIRL” is a Gothic thriller recalling 70s arthouse horror, with themes of queerness and women’s sexuality as corrupting forces.

Welcome to Sapphic Sundays, Morbidly Beautiful’s newest bi-weekly column all about my very favorite topic: queer ladies in horror. Every two weeks I’ll be examining a different film that features women who love women, from modern movies where their queerness is explicitly defined to older flicks where it’s all subtext and subtle clues. My focus will be on the representation of queerness in these films, how it informs the characters’ place in the overall narrative, and what messages are being sent about women’s sexuality.

It’s no secret that the relationship between horror and queerness is historically problematic, but, by critiquing these narratives, my hope is to shine some light on their recurring themes and why they are so prevalent — and why so many queer women, myself included, find enjoyment and even empowerment in them.

The first film I’m digging into is Sweet, Sweet Lonely Girl, written and directed by A.D. Calvo and currently streaming on Shudder.

The story follows “sweet, lonely” Adele, a young woman who hopes to escape her uncomfortable home life by moving in with her reclusive aunt as a live-in caregiver. The move only isolates Adele more; she has no friends and virtually no human contact. Her only communication with her aunt comes in the form of one-sided conversations outside her locked bedroom door and the strict orders and grocery lists her aunt slips underneath.

Then she meets Beth: a vibrant, sexy, and dangerous woman who takes an immediate shine to the timid Adele. Adele’s world soon revolves around Beth to the exclusion of everything else, including her aunt’s needs.

Torn between a sense of duty toward her aunt and the allure of Beth’s free-spirited lifestyle, Adele finds herself cracking under the weight of her desire to please them both while still maintaining her own sense of self. When her choices eventually turn fatal, the sinister thread that’s been pulling her along snaps and Adele’s world comes crashing down around her.

Sweet, Sweet Lonely Girl starts out as a psychological thriller in the style of 1970’s arthouse horror.

Visually and thematically it’s an homage to films like Let’s Scare Jessica to Death and Robert Altman’s Images; both films are about the slow disintegration of a woman’s sanity as she is haunted by another woman who may or may not be real. The film also recalls the work of Jean Rollin — minus the gratuitous nudity. The Gothic atmosphere, soft sensuality, and focus on intimacy between women are all hallmarks of Rollin’s vampire films.

While Sweet, Sweet Lonely Girl is not about vampires, it relies heavily on many tropes of the lesbian vampire films of the 1970’s, particularly in its portrayal of the relationship between Adele and Beth.

Adele is the “good” girl to Beth’s “bad” girl. From the beginning, this dichotomy is highlighted by their physical appearances. The fragile, innocent Adele is pale, blonde, and waifish. She dresses in neutral colors and plain clothing that covers her entire body. She’s unassuming and unassertive; she secretly wants to be seen but has found that it’s safer to fade into the background.

Beth, on the other hand, has darker hair, darker skin, and wears bold, dark clothing and heavy makeup. She stands out effortlessly, holds her head high, and carries herself with confidence that Adele can only dream of. While Adele is bound by her responsibility to her aunt, Beth is “free.” “She doesn’t care what anyone thinks,” Adele observes. “I wish I was more like Beth.”

The two become fast friends and Beth’s influence over Adele starts to grow. Adele finds herself doing things she never would have done before. It starts innocently enough, but the repercussions are immediate. While playing dress up in the basement with Beth, Adele forgets to bring food to her aunt. Soon she’s stealing money and skimping on the grocery list so she can pocket the extra cash. The tipping point comes when, at Beth’s insistence, Adele trades her aunt’s expensive prescription heart medication for a cheaper over-the-counter alternative, a move that directly leads to her aunt’s death.

Throughout horror’s long history, queer women are often portrayed as predatory.

In traditional lesbian vampire narratives, the vampire is a corrupting force who tempts otherwise “good” women into a life of sin. What makes her so dangerous is the fact that the world she offers — immortality, freedom from society’s restrictions and expectations — is much more appealing than the boring, mortal existence of her would-be victims.

Beth offers Adele a carefree life away from the demands of her family, but her influence never feels as liberating as it should.

Adele is constantly anxious over the choices she makes; she wants to do the right thing but she also wants to be with Beth and it’s clear that the two are mutually exclusive. Her guilt colors otherwise pleasant experiences, but it isn’t just her moral dilemma that causes problems. The freedom that Beth offers Adele is far from free.

Instead of being free to be herself, Adele becomes more like Beth. She merely trades the pressure to live up to her family’s expectations for the pressure to keep up with Beth’s lifestyle.

The stark visual contrast between the two women fades as they slowly become what Andrea Weiss, in her book Vampires and Violets: Lesbians in Film, calls “narcissistically matched.” Adele starts wearing makeup, jewelry (stolen from her aunt), and darker clothes. Beth erases the things that set Adele apart from her, until, in the end, Adele is literally just an empty shell.

The film’s bizarre ending nosedives into supernatural territory.

But the exact nature of the entity — that is, Beth — at play isn’t directly addressed. She consumes Adele’s life force, presumably to sustain her own. Unlike the vampire, she doesn’t offer Adele a glamourous afterlife but instead leaves her hollow, a shadow of her former self.

Sweet, Sweet Lonely Girl is full of some very not subtle imagery that highlights the darkness surrounding Beth and her relationship with Adele: pomegranates, an underlined Bible passage about corruption, a statue of Pazuzu next to the bed where the two of them spend the night together. All of this emphasizes the destructive nature of their relationship and gives the whole film the air of a cautionary tale that warns against everything Beth represents, sexual agency most of all.

Beth’s overt sexuality is meant to contrast Adele’s inexperience, yet she shows no intention of having sex with Adele. From the beginning their friendship is physically intimate, full of heated gazes and gentle touches; they lie together and kiss, and Beth tells Adele that she loves her.

But when Adele tries to initiate sex, Beth pulls away. “I’m not really…” she says, as if she means to say: “I’m not really like that.” The next day she invites a male friend over, thus driving home the point that she is not like that. Later, Adele tells her, “I thought we were together,” and Beth’s response is almost flippant. “Together? You mean like…” Again she trails off, avoiding words like “gay.”

Of course, it’s all part of her plan to destabilize Adele and leave her confused and vulnerable so she can strike, but it underscores the idea that women — especially bisexual women — are cruel, flighty teases.

Adele’s sexuality is a little more straightforward but fraught with its own issues.

Her preference for women may stem from trauma. Any time she’s around men she is visibly uncomfortable, looking over her shoulder, and we see her on the receiving end of some very dubious looks from her stepfather. She seems to be uncomfortable with being touched by anyone, but warms quickly to Beth’s physical nature only to be rejected when she finally opens up.

After Beth’s rejection, Adele brings a man home and has sex with him, and it’s clear she gets absolutely zero pleasure out of it. This encounter is the last step in her quest to “be more like Beth,” and it’s the proverbial nail in her coffin.

SWEET, SWEET LONELY GIRL makes no attempt to rewrite the playbook on queer women in horror, preferring instead to pay homage to the earlier films that inspired it without subverting the traditional themes of those films. Which is fine; it’s still enjoyable if you’re a fan of dreamy mid-20th Century arthouse aesthetics, slow burn storytelling, and pretty ladies making out in graveyards.

Unfortunately for this film, there are half a dozen Rollin titles that fit this description I would rather watch instead — and I’ll be discussing one of them next week!

Follow Us!