Understated and deeply personal, “Leap of Faith” offers a powerful communion for devotees of “The Exorcist” and eccentric auteur William Friedkin.

I’ve been thinking a lot about death lately, but don’t worry; I mean the random, ruthless kind.

This is my first Shudder Sunday in a month, probably the longest gap since I started the column a year and change ago. I have an excuse, though, so hear me out. Not long after my write-up on Salem’s Lot, a good friend of mine died. Your mind probably went to the same place mine did when I heard, but no. It had nothing to do with that biological wildfire that keeps on racking them up like a Now Serving number from hell. This was a fluke. A bolt from the blue. One morning fine. The next, non-existent.

My dad passed away when I was younger. I wrote about that and him and me in my review of the Visitations podcast. He died 13 years ago, when I was 13. My friend died a few weeks ago, not much older than I am. A week after that, I ended up in the ICU with heart problems nobody in the white coats could put their gloved fingers on. My only experience with that part of the hospital prior was when dad went in with unexpected heart problems and never came out.

“In many ways, I think biology is destiny,” says William Friedkin, director of The Exorcist and focus-cum-philosopher of the Shudder-exclusive documentary on its making.

I hesitate to call it a “making-of,” though it is by any logical definition. That just sells it short as a one-man conversation. If anything, given the stained-glass shadows of Catholicism that color it, it’s closer to a confessional.

Laying there alone — a non-negotiable mandate given that wildfire constantly raging in our peripheral vision — I worried about the poetry of me going so similarly to dad. My family must’ve noticed it, too, given the broken glass in their throats on otherwise mundane calls.

It’s how I’d write it if I had to, if I wasn’t the one afraid to fall asleep. To paraphrase George Lucas, another filmmaker profiled by documentarian Alexandre Philippe, it rhymed.

Friedkin starts the doc by splitting the universe in two: “Everything has to do with the mystery of fate or faith.”

They are, in the end, question and answer. What’s going to happen? and I believe I know.

The Exorcist may be a film about faith, but 47 years later, the iconoclastic filmmaker has fewer answers than ever on the subject. Fate, on the other hand, he sees as clearly as the Vermeers and Rembrandts that keep his blood pumping.

Philippe lets him talk. The subtitle, William Friedkin on The Exorcist, is both accurate and understatement. The few instances where we hear questions off-camera are invisible enough to maintain the illusion: this is a one-man show.

William Friedkin has regained a reputation in the last few years. He doesn’t make movies often anymore — 2011’s Kentucky-fried black comedy, Killer Joe, was his last narrative feature — but podcasters and other filmmakers have made him more present than ever. 2018’s Friedkin Uncut turned the iconoclast loose on his own career, the Uncut part bordering on shameless; there’s a fine line between unfiltered perspective and ending your reverent documentary with the subject opining on film festival juries: “Fuck them and the horse they rode in on and the ship brought them over here and the dog that walks behind them. Fuck them all!”

Friedkin never goes that far in Leap of Faith.

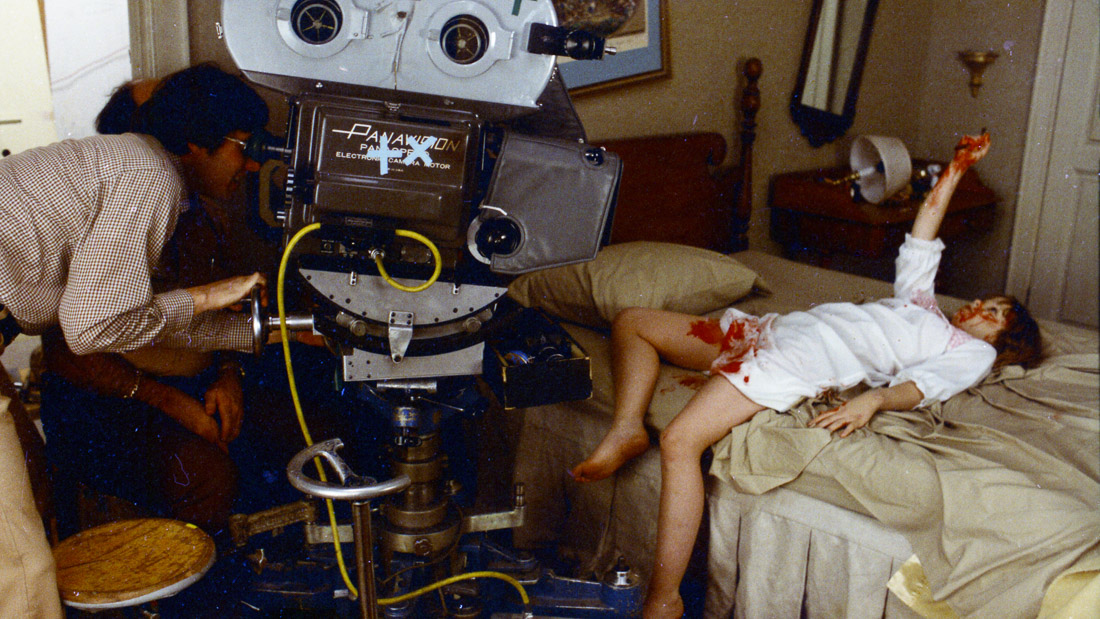

It’s a quieter, gentler discussion than devotees might be expecting from the mythical madman of New Hollywood. His more questionable means of directing go unmentioned — the Exorcist episode of Shudder’s Cursed Films series makes a worthwhile companion piece on the matter — but the few that he brings up, like firing guns to properly startle actors, are treated as tradition and impulse.

He’d seen another filmmaker do it in a magazine. It seemed like the right thing to do at time. Not quite apology, though he does admit it would get him dragged off set today.

Fritz Lang, looking in an archival interview like the hardest filmmaker who ever lived, calls it “Sleepwalking security.” Doing what you’re doing because you believe it’s the right thing to do. Friedkin credits instinct more than once. Faith is a fair synonym.

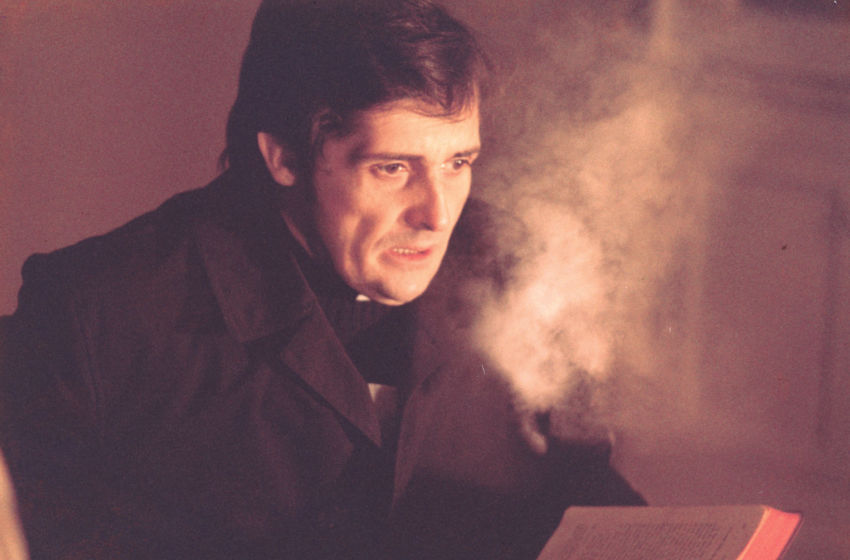

Father William J. O’Malley, the actual Jesuit priest Friedkin cast on a hunch as Father Dyer, couldn’t cry on camera. Friedkin, thinking fast, asked the man if he loved and trusted him. O’Malley said he did.

The director punched him square in the face and pushed him back into frame.

O’Malley cried. they got the take, and as soon as Friedkin called cut, he thanked him for it.

Without ever connecting the dots, William Friedkin summarizes the relationship between God and His followers.

It’s fundamental doctrine — the Mysterious Ways clause — and not even exclusive to Christianity.

When dad died, it came like a chorus. God has a plan. Don’t lose faith. It was painful and jarring and the scar will never fade, but it happened for reasons beyond human comprehension. As a Lutheran school kid who had to write that refrain long-hand on various tests and quizzes, I bought it without much trouble.

A week and 13 years removed from very different deaths, I was having a harder time with it.

“There’s no one technique,” says Friedkin, offering his own take on those Mysterious Ways. Despite what his perceived ego or provided anecdote might suggest, he’s just a man who decked an actor. There’s no justifying that without an amorphous higher power. Instinct. Faith. Fill-in-the-blank.

The practical lesson of Leap of Faith is that no movie can be made without faith. The spiritual lesson is that the great ones are made that way by fate.

By his count, it was all fated.

The timing of William Peter Blatty sending his novel to him. The chance that he saw Jason Miller on stage. The luck of finding an Iraqi archaeological crew that didn’t mind the production. Friedkin goes on convincingly across the entire documentary, until it veers away from The Exorcist.

It’s just as much about the man as it is his most famous movie.

With nostalgic veneration, he recalls the films and morbid curiosities that shaped his childhood. One story involving a yard down the street littered with the limbs of a homicide victim is especially vivid.

Friedkin loses his showman spirit when he talks about friends lost, dead or otherwise. Blatty, who recently passed in 2017, still gets the present-tense. Composer Lalo Schifrin, who’s still working today, is treated like a ghost. The two friends haven’t talked since the director rejected his Exorcist score. It takes Friedkin a moment to recover after admitting as much.

I couldn’t shake the loneliness in that hospital bed. Part of me still can’t. I worry I’ll wake up back there, pinched out of a pleasant dream by my blood pressure cuff. It’s something I told myself I’d swallow and let eat away at me, should it be so acidic.

For a documentary most will watch for behind-the-scenes trivia, Leap of Faith dwells in a familiar loneliness.

As the celluloid glory fades, Friedkin starts to sound like a man trying to make sense of a miracle while he still can.

Anyone expecting the make or model of freezer they shot the climax in will be sorely disappointed, but there are lessons still, for filmmakers and normal folk, about grace notes. By Friedkin’s definition, they’re more important than the big events. He relates them to quiet foreshadowing in the film at first — kids dressed as terrible things for Halloween portending something terrible dressed up as a kid. By the credits, it’s nakedly personal, a Zen garden that taught him what it is to be alone decades earlier.

If that sounds like a bummer, it might be. This isn’t a leave-on-in-the-background watch. But I found some hope in the ending. Not of the doc, but The Exorcist.

“It isn’t even clear to me as I sit here what the hell happens.”

Take away all its records and plaudits and legacies… and William Friedkin still doesn’t accept the ending of The Exorcist.

Father Karras brings the demon into himself with an evil act, beating an innocent child. As soon as it takes hold, he infamously sacrifices himself by jumping out the nearest window and tumbling to his death. It’s suicide any way you measure it. The demon loses. Karras wins.

The final, triumphant act is a cardinal sin of Roman Catholicism. How can it be? What sense does that make?

“The moment is a compromise.”

It’s the only ending there is, somewhere between fate and faith.

I’m alright now. I have to take little white pills now and again, like Father Merrin does. Fortunately, because life is not a movie and need not rhyme, mine aren’t shorthand for impending doom.

Filmmaking documentaries are comfort food to me. I’ve reviewed more than a few for Morbidly Beautiful. And Shudder, to its credit, has more than a few essentials.

Leap of Faith is another on that list, with an asterisk. It’s entirely possible somebody could watch it and walk away underwhelmed from the meanderings into abstract art and Citizen Kane. But it found me at the right time and gave me enough peace to write again.

Fate and faith.

Follow Us!