“Sator” is a deeply personal, dread-inducing masterpiece of minimalist horror exploring the terrifying effect of hereditary mental illness and isolation.

Sator is an extraordinary cinematic achievement, both for the haunting and hypnotic magic that transpires on screen as well as the heroic, behind-the-scenes efforts of John Graham to bring his singular vision to life.

Five years in the making, Graham wore practically every hat imaginable in the production of this deeply personal project — including writing, directing, editing, producing, and even scoring the film. He also served as production and costume designer, sound designer and mixer, and makeup, visual and special effects artist. He even single-handedly built the cabin that served as one of the primary set pieces in the film.

As critics and fans of truly independent filmmaking, we often find ourselves making certain allowances for passion projects made using very limited resources. We understand that there are technical limitations, and we don’t expect these films to look and sound as good as those with studio support and access to the best talent and equipment. In fact, we tend to grade those films on a curve — focusing more on the effort involved rather than solely the quality of the output.

But every once in a while, a film comes along that obliterates that curve and proves how much can be done with very little when the right talent is involved — when a filmmaker comes forward with both a startlingly original vision and exceptional technical expertise.

Sator is a shining example of a film that belies its humble origins and, though a tightly contained piece of minimalist horror, feels remarkably polished and masterfully executed.

But as impressive as the story of how this film got made is, perhaps even more intriguing is why the film evolved the way it did, inspired by very personal events in Graham’s own life.

On its surface, Sator can be viewed as a supernatural horror tale about a demonic entity that has terrorized an innocent family for years, leaving death and destruction in its path. However, it’s clearly an allegory for the devastating effects of hereditary mental illness, an important subject matter Graham is all too familiar with.

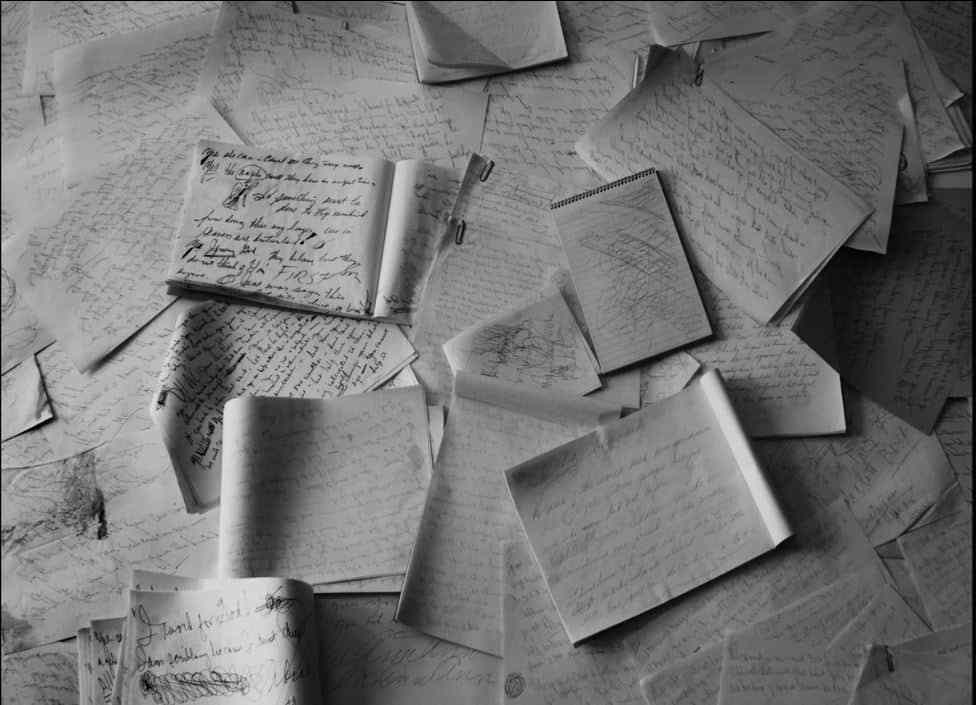

His grandmother (like both his great-grandmother and his great-great-grandmother before her) spent time in a psychiatric hospital as a result of hearing voices in her head — voices that told her to do things. The most prominent voice was one she referred to as Sator. This being would communicate with her via “automatic writings” in which she would go into a dream state or trance, with pen in hand, while Sator took control and began writing for her.

Graham only discovered this bit of dark family history when he found his grandmother’s journal during the making of the film.

Originally, his grandmother (June Peterson) was only going to have a very small part in the film. But, as excited as she was to have her grandson shooting a film in her home, her dementia would cause her to forget the people around her were actors as soon as the camera started rolling. For this reason, Graham had to shoot her scenes without feeding her any lines — never knowing exactly where her unscripted dialogue would take the story.

Once she began to talk openly about the spirits in her head, he knew the story’s focus had to change. And the script was quickly re-written in the middle of shooting. However, the most significant rewrite came when the film was in post-production. While Graham knew Sator was his grandmother’s ‘guardian’, he didn’t know much more until she had to be moved in a care home after he finished shooting. While cleaning out her house, he found two huge boxes hidden behind a chair on a bookshelf.

One box had all her automatic writings that his family thought she had burned, and the other was a thousand-page journal describing her journey with ‘Sator’, who led her to a psychiatric hospital. He decided ‘Sator’ needed to be a part of his film, so he rushed to get all the information he could out of his grandmother before dementia fully took over.

The resulting film is moody, bleak, and haunting — a dark tale of isolation and one man’s battle with his own inner demons and struggle to retain his sanity.

The desperate man on the verge, played virtually dialogue-free by Gabriel Nicholson, is named Adam. Living alone in a small, sparsely furnished cabin deep in the woods, he spends his days hunting and meticulously combing over deer cam footage. However, we soon discover it’s not the image of deer he’s obsessed with capturing.

His isolation is only occasionally interrupted by visits from his brother Pete (Michael Daniel) and brief contact with his sister Evie (Rachel Johnson) and their grandmother Nani (June Peterson). Nani is suffering from dementia and often can’t remember her family, but she remembers everything the spirit Sator has said to her. She speaks fondly of Sator as a watchful caretaker, but Adam lives in fear of the entity, convinced it has its malevolent sights set on him.

There are not-so-subtle hints that this family’s disfunction extends even further, with a grandfather who died under mysterious circumstances and a mother who has simply disappeared without a trace.

Adam spends his nights listening to old cassette tapes of his mother pontificating about Sator, filled with foreboding messages about the spirit’s intentions.

“After you have suffered a little while, he will find you. He will make you pure.”

Without uttering a word, Nicholson conveys so much fear, paranoia, and pain during Adam’s slow descent into madness.

His downward spiral is marked by disturbing visions, whispers from disembodied voices, and haunting dreams. As we move back and forth between the present and the past — shifting from highly saturated, widescreen shots of breathtaking landscapes to grainy, black-and-white flashbacks shot in 4:3 aspect ratio — we’re left disoriented and drawn into Adam’s increasing instability.

With its non-linear storytelling and fractured narrative, Sator demands patience and attention from its viewers. It’s not a film you can casually watch while distracted. Combined with the film’s slow pace and minimalist approach to horror, it’s likely to alienate many viewers.

However, for those with a taste for slow-burning, atmospheric horror — the kind that relies on creeping dread rather than frequent jump scares — SATOR is enormously satisfying. Graham has a remarkable way of infusing every scene with unbearable tension, as the film slowly and unsettlingly simmers until its shocking and explosive final act.

With its eerie sound design, exceptional cinematography and visual provocation, Graham manages to make even the mundane horrific.

He creates a disturbing hellscape where every encounter feels like an otherworldly harbinger of doom.

There’s an obvious personal core to this film, and the casually chilling way Peterson recounts her experiences with Sator makes this a unique and terrifying genre experience. Whether or not Sator is real or merely a manifestation of deteriorating mental health, the haunting effect is the same. Because, as anyone who has ever struggled with mental illness or been affected by it knows, there’s nothing more terrifying than a fractured mind.

Given the enormous talent and potential Graham showcases in his impressive debut feature, I can’t wait to see what he does next, especially with more resources at his disposal. Fortunately, he’s already completed work on his next screenplay, which he says was heavily influenced by auteurs such as Ari Aster, Gaspar Noe, and Lars Von Trier.

Trust me, this is someone genre fans are going to want to keep their eyes on.

Follow Us!