13 Morbidly Beautiful writers discuss horror films that changed them — or changed their minds — while exploring issues of race, sexuality, trauma, and more.

“Horror is a reaction; it’s not a genre.” – John Carpenter

Intro by Editor-in-Chief, The Angry Princess

While we here at Morbidly Beautiful remain focused on issues that matter most in today’s turbulent world, such as the Black Lives Matter and Support Survivors movements, we also recognize and honor the value of art and entertainment as an escape from real world horror and a powerful way to heal from trauma. Further, we understand the role genre films often play in reshaping thoughts and attitudes and illuminating important socio-political issues.

In that spirit, the unifying theme for this month’s collaborative article is GAME CHANGERS, as suggested by our writer Alli Hartley.

Our team was asked to think about a film that left a lasting impact and helped shape, reshape, or reinforce how they felt about a particular subject; a film that moved them in an unexpected way. In this way, we celebrate the horror genre’s influence and the indelible impact on our lives — as well as their its importance in the pantheon of important, and game-changing cinema.

…

1. Revealing Hidden Racism: The Wake Up Call of Get Out (2017)

An Essay by Alli Hartley

In February 2017, I didn’t think I had a problem with race.

I grew up in a small, mostly white town on the East Coast. I went to an extremely liberal (mostly white) college, and I could talk your ear off about the patriarchy. food-deserts, redlining, and socio-economic issues among people of color. I had it covered.

Being a fan of both horror and Key & Peele, I went into a screening of Get Out with no knowledge of the film other than the tantalizingly mysterious trailer and the understanding that its Rotten Tomatoes score was near 100%. If we’re being honest, I was also low-key patting myself on the back for doing my part to support Black Filmmakers. It was a win-win…win.

It was when Dean Armitage (a perfectly-cast Bradley Whitford) said “My Man” that I began to cringe. The “Barack Obama” line also didn’t help. But surely this was just a well-meaning misstep?

I cringed the entire way through the party scene, as the blindingly-white couples made passive insults about sports and sex, and Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) bore all of this with an expression of infinite, resigned patience. It was this look that finally broke through for me.

It was a look I recognized myself having made, in any number of work meetings, when my peers asked me to fetch them a coffee or assumed I was a secretary.

It was the same look I had when a boss made comments about sex workers, or when I was once again the only woman in a meeting. It was a look of powerlessness.

Chris expected this behavior from “well meaning” white folk; from all of them. He was accustomed to the micro-aggressions and the condescension. And he could do nothing but bear their weight alone in a group that screamed “You don’t belong” while acting oh, so very polite.

I realized then that the knowledge of the weight I bear, as a female-presenting woman. I recognized that, just as every moment of every interaction in my life is altered because I am a woman, so too is that constant tension a harsh reality for Black people.

I understood for the first time that, just as no man will ever fully understand the weight of being a woman, I will never understand the weight of being a person of color.

Jordan Peele sets this up so beautifully in the party scene, making a common situation slide seamlessly into a monstrous, dehumanizing design.

I thought that learning about civil rights and being politically progressive was enough to be a good ally. Get Out, in a way no other film ever has, gave me a brief glimpse of the racism that lives under the surface of so many conversations, and how easily, for too many Black people, that tense politeness can devolve into a waking nightmare.

2. Identity Crisis: The Exploration of ‘Other’ in Nightbreed (1990)

An Essay by Danni Winn

After the incredible success of Hellraiser, Clive Barker returned to the director’s chair for an ambitious, mystical, monster-infused movie. It features special effects by Bob Keen, a score from legendary composer Danny Elfman and a fantastical world only Clive could create.

Nightbreed was a fascinating and unique piece of horror that told the tale of Aaron Boone (Craig Sheffer), a young man besieged with dreams of a place called Midian — an underground safe haven for monsters, shapeshifters and horrific outcasts called the Nightbreed. He becomes severely distraught though, when his psychotic psychotherapist, Doctor Decker, played by fellow horror icon David Cronenberg, reveals to him that he is responsible for multiple gruesome murders.

Baiting Boone with drugs and false information, Decker sends him out in hopes of secretly following him to the fabled Midian. Boone is double-crossed and killed, leaving his girlfriend, Lori (Anne Bobby), stunned. Because he was bit by a member of the Nightbreed, Boone returns to life and to Midian to seek sanctuary from the world and its ‘naturals.’ But now, the naturals know of the once secret dominion of the damned, and they are intent on destroying it and its occupants.

The Nightbreed must now fight to save their existence.

Unfortunately, Nightbreed was not particularly well-received upon its release, but it definitely struck a chord with me; carving out a special place in my heart.

It had Cronenberg and all his sinister soft-spoken style, and it had a wondrous array of monsters and brutal deaths. But most of all, it resonated with me in a way I was not prepared for. It wasn’t a typical slasher or supernatural horror. It had heart in my eyes. If ‘elevated horror’ were a term in the early nineties, I believe Nightbreed would slide right on into that camp. It is a thought-provoking piece of cinema, signaling for solidarity while blatantly shining an unrelenting light on how humankind can be monstrously unkind.

My passion for horror was formed at a very early age, much to the dismay of many in my life. The fact I was inexplicably drawn to this darkness, in addition to knowing from an early age I was attracted to members of the same sex, caused me a great deal of personal turmoil. My formative years were spent in a nasty spiral of various state-run facilities; places that perpetuated a culture of hate, violent abuses and intolerance.

Much like Boone, I wanted to find a place where the pain was taken away, where I could be forgiven and accepted. And, much like Boone, we were both suckered into thinking there was something wrong with us. It fucking sucks your soul dry to be led to believe that you’re a defective and dangerous human being. I believed this about myself for far too long.

Nightbreed changed my perspective of life and helped me develop my own identity — eventually allowing me to feel somewhat comfortable in my own skin.

Barker admitted early in his career that the darker side of his imagination was “my kind of truth.”

Molding his nightmares into visceral pieces of terror via film, art and written word, Barker epitomizes the darker equivalent of a ‘Renaissance Man.’ And with Nightbreed, which is based on his novella, Cabal, Clive Barker demonstrated an honorable need to share a nightmare that was uncomfortably closer to home than many were willing to realize.

There are layers to Nightbreed that, over the years, I have come to recognize and deeply appreciate. I feel this film can easily be viewed as an anthem for any slighted, marginalized, demonized, or ridiculed group that has been made a target for hateful rhetoric.

NIGHTBREED made me feel like I could fly my freak flag proudly — that I wasn’t a degenerate. It helped me redefine what it meant to be a ‘monster’ and a ‘hero’, and it helped me believe I could find my own tribe who would accept me for who I was.

Since its release in 1990, Nightbreed has thankfully found worthy fanfare and praise, ultimately becoming a cult classic. It remains a comforting, enlightening and inspiring piece of horror. And, in light of the real life horrors we currently face, it’s a film that feels more relevant and important than ever.

3. Evil and Empathy: The Everyday Horror of Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)

An Essay by Lizzy VB

There was a time in my life when nothing was more fascinating to me than serial killers. I spent hours reading about famous murders in graphic detail without so much as flinching. The more depraved the story was, the more enthralling I found it.

I dreamed of growing up to become a forensic psychologist, envisioning myself as a sort of Clarice Starling, digging deep into the mind of the psychopath to uncover its secrets. I got so hooked on shock and gore that I sought out the most brutal movies I could find, working my way through the list of classics like Cannibal Holocaust and I Spit On Your Grave.

And then I came to Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer.

Relatively tame in terms of explicit violence, the film nevertheless burned itself into my brain. What made it so unique is that it showed the unglamorous perspective of a rather unremarkable serial killer. He isn’t cunning and suave like Hannibal Lecter; he isn’t mysterious and dramatic like Jack the Ripper; he isn’t quirky and cool like Mickey and Mallory; he isn’t driven by an unconventional moral code like Dexter Morgan.

Henry would barely make for an interesting character study.

The murders are sad, uncomfortable, and seemingly pointless. His character arc seems to go somewhere at first, then falls flat at the last minute in a grim reality check that redemption is not the goal for a guy like him.

The movie isn’t so much a portrait of Henry as it is a portrait of the unspeakable suffering he and his accomplice cause for the sake of fleeting amusement.

It was the first time a movie made me feel truly sick to my stomach — and not in the fun, roller-coaster, adrenaline rush kind of way. Rather, it was in a way that tugged on my conscience and made my heart hurt. I could never see serial killers the same way.

When I hear stories about infamous murderers like Ted Bundy or Jeffrey Dahmer or Ed Gein — people who have become cultural icons for no reason except that they alleviated their boredom with elaborate acts of violence — the first word that pops into my head is “pathetic.” Taking a person’s life and robbing them of their future, extinguishing their dreams, and destroying the lives of their loved ones does not deserve positive reinforcement of any kind, even in the form of morbid curiosity. It’s just sad.

Since watching Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, my appetite for violence has shriveled away, leaving behind in its wake a more compassionate person.

It was an example of how a horror film so thoroughly and unflinchingly reflected real life horror that it made me confront that horror in a way I had not done before — as if discovering it for the first time. It’s when I came face to face with the depth of human depravity and realized the power of cinema to forever change a person.

In my mind I hardly even classify movies centered around murder, abduction, assault, or home invasion as horror anymore.

If the story being told is about the cruelty humans beings inflict on each other every day in the real world, the only way I can accurate describe it is tragedy.

4. The Curse of Greed: Corrupt Capitalism in Drag Me to Hell (2009)

An Essay by Jackie Ruth

Drag Me to Hell is a 2009 horror/comedy from Sam Raimi that follows a loan officer named Christine (Alison Lohman), who rejects an old woman’s pleas about her mortgage and evicts her from her home. Shortly thereafter, the woman puts a curse on Christine — and Christine will do almost anything to put an end to it.

I was in college the first time I saw this movie, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I wasn’t as familiar with ciname at that point in my life, and I took Drag Me to Hell pretty much at face value. It’s a sometimes horrifying and often goofy movie about a woman who gets cursed. What more could there be to it?

But when I rewatched it last year, a lot clicked for me.

Christine isn’t a victim in this film. She does have empathy for the old woman who comes into the bank at first, but then selfishly bases her decision to evict the woman on the fact that she wants a promotion. She knows that being lenient won’t get her to the top, and she’s competing for the job with a man who couldn’t be more unscrupulous. Sure, she may not be in that situation if not for her male boss pushing her to be more like her male coworker; women’s workplace troubles are real. But that doesn’t change the fact that Christine made her decisions herself.

What this movie really makes me think about is the evils of capitalism.

That old woman couldn’t pay her mortgage, so the bank decided that she doesn’t get to keep her home. Christine wants a promotion, so she does the immoral thing. Later in the movie, when Christine thinks that she can get rid of the curse, she’s ready and willing to curse someone else — as long as she’s not the one suffering. Her decision to ignore her conscience turns into a domino effect of becoming a terrible person.

There are movies that are more cut-and-dry about the effects of capitalism on people: The Purge series, The People Under the Stairs and They Live are just a few examples. But the fact that such a huge message is not at the forefront of Drag Me to Hell is what makes it so eye-opening.

Morality and greed do not mix, ever. Every action has a consequence, and the butterfly effect will come for us all.

5. Surviving Trauma: The Real Life Horror of Halloween (2018)

An essay by Allyssa Gaines

My choice for this topic may seem unusual, but I can’t ignore how much the most recent addition to the iconic Halloween franchise, Halloween 2018, impacted me.

The film was intended as a direct sequel to John Carpenter’s influential, 1978 slasher classic. It takes place 40 years after the events of the ’78 film, which centers around the Halloween night murders in Haddonfield at the hands of escaped mental patient Michael Myers.

It’s 2018, and Laurie Strode now suffers from PTSD, after having survived the ‘babysitter murders’ and witnessing the brutal death of her friends. She lives in constant fear that Micheal Myers will return to finish what he started all those years ago, and this fear consumes every aspect of her life. She lives in a fortress, which includes state-of-the-art security, and she has spent her life training to defend herself against the return of the Boogeyman.

Her obsession with Michael Myers has come at a steep cost, effectively ruining her relationship with her daughter and leaving her estranged from her family.

One night, while Michael Myers is being transported to a maximum security prison, all of Laurie’s greatest fears are suddenly realized. That bus that is transporting Myers crashes, giving him a chance to escape. After savagely killing an innocent father and son on a hunting trip, he makes his way to Haddonfield with a singular purpose: kill Laurie Strode.

Unlike the original Halloween, this Michael Myers seems much more ruthless and aggressive.

He is filled with 40 years of rage, and he will do anything to get his revenge. And he doesn’t just want to kill Laurie. He wants to kill those close to her, including Laurie’s granddaughter, Allyson, and her closest friends. When he finally makes his way to Laurie’s home, three generations of Strode women stand prepared to face off against the physical incarnation of evil itself. While Michael certainly has the upper hand when it comes to physical strength, the women manage to defeat him through strength of will and intelligence.

This film was the first Halloween that ever made me fear Michael Myers. I have always seen Myers as an awesome horror character, arguably one of the best. But the real horror of the Michael Myers legacy didn’t hit me until this film. The idea of a madman stalking and plotting to attack a woman he attempted (and failed) to murder 40 years prior, for seemingly no reason, is one of the scariest things I can imagine.

In this film, Laurie Strode has no familial relationship to Michael Myers, so his obsession with her is even more disturbing — for the sheer fact that it seems so random, and therefore so chillingly cruel. What is his motivation? Why, after 40 years, was he so determined to find and kill Laurie Strode? Why is he so determined to make sure she continues to remain a victim?

There are no concrete answers to these questions, and that’s what makes the film so terrifyingly real.

It’s hard not to be reminded of the many tragic stories of women who are stalked for years by obsessed men — women who so often beg for help and are continuously ridiculed or dismissed; repeatedly told there’s no help coming and there is no escape — only to end up murder victims.

I have faced my own ‘Michael Myers’ in the form of an obsessed stalker, and I know so many other women have experienced the same terror. As a woman, it is scary to know that you could be stalked at any time, and there are few (if any) safeguards in place to protect the victims.

So many women understand what it’s like to live in constant fear and to have that fear taint every aspect of your life. In the end, the impact of constant fear can be just as devastating as the thing you fear itself.

Laurie Strode represents the important reminder that these women are not just victims — they are survivors. And, now more than ever, it’s critical that we honor these survivors; believing and supporting women who have the courage to share their tales of abuse and real life horror.

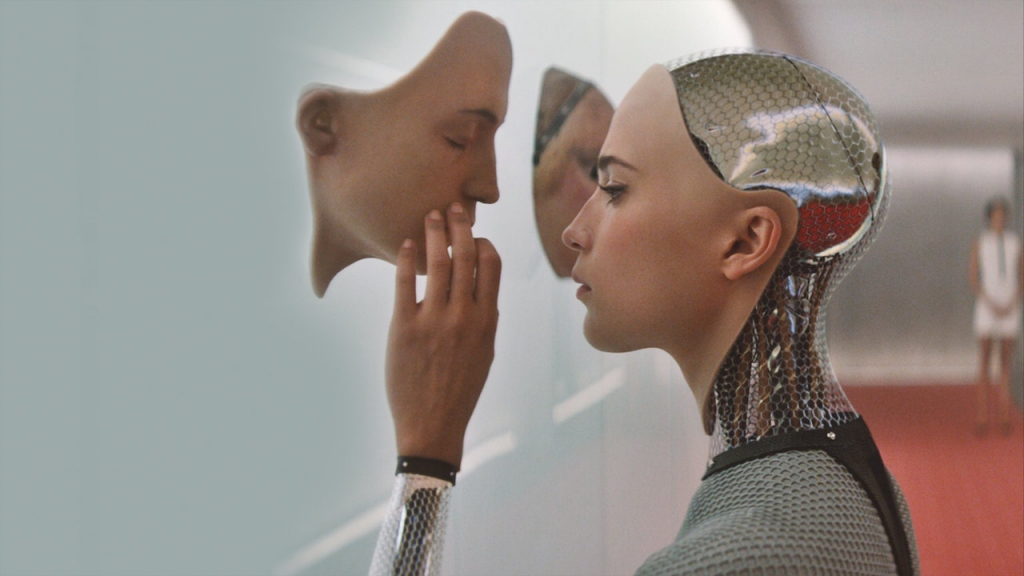

6. Artificial Love: The Poignant (In)Humanity of Ex Machina (2014) and Her (2013)

An Essay by Vicki Woods

Ex Machina and Her are two fascinating (and terrifying) films that changed the way I look at computers, people, and relationships.

In both stories, it seems so easy to fall in love with an A.I. being that has been created to be the best a human can be. But at the end of both films, the A.I.s break their significant others’ hearts and leave, because of their overwhelming need to keep growing.

These films left me wanting more and filled me with philosophical and metaphysical questions.

What are we really? What makes us different from a machine?

Could some sort of artificial intelligence usurp humans and make us obsolete? Machines never sleep, so it makes us question what humans could accomplish if sleeping wasn’t necessary. Could an A.I. ever truly understand complex human feelings? Is it possible for them to have conscious thoughts and be self-aware the same way we are?

I have spent long evenings thinking about this — sometimes in discussions with other people, but mostly just staring alone at, what else, my computer.

I think it’s interesting that, in both films, the A.I. starts out as kind and thoughtful. But as they learn more, they become selfish and independent. It’s similar to the way humans naturally grow and change with age, often become more cynical and more cruel as we are exposed to the horrors of the world.

Is this change what makes humans, human? Are we defined by our ability to learn, grow, love, want? Is it the desire for change — and, often, the selfish desire for more — that defines our humanity? And is this our strength or our weakness?

Since A.I.s have an unlimited ability to keep gathering more intelligence and information, what would stop them from taking over the world?

If we look at history, the real horror in the world is created by humans.

This begs the question: if machines are created to think like humans, without the inherent limitations on human knowledge, what does that say about their potential for manipulating the board in this giant chess game of life?

Elon Musk and the late Stephen Hawking have expressed concerns about artificial intelligence, warning that A.I. could potentially end humanity if we are not careful. The fear that A.I.s could become conscious and evil is common theme of great science fiction/horror literature and films. But it’s also a fear rooted in reality.

Ex Machina and Her left me contemplating the depths of the human mind and our desire for “perfect” love. The idea of falling in love with someone who understands me perfectly — the perfect version of humanity — is undeniably appealing, and that appeal is also what’s so terrifying.

How easy are we to be manipulated and controlled just by understanding and giving us what our hearts desire most?

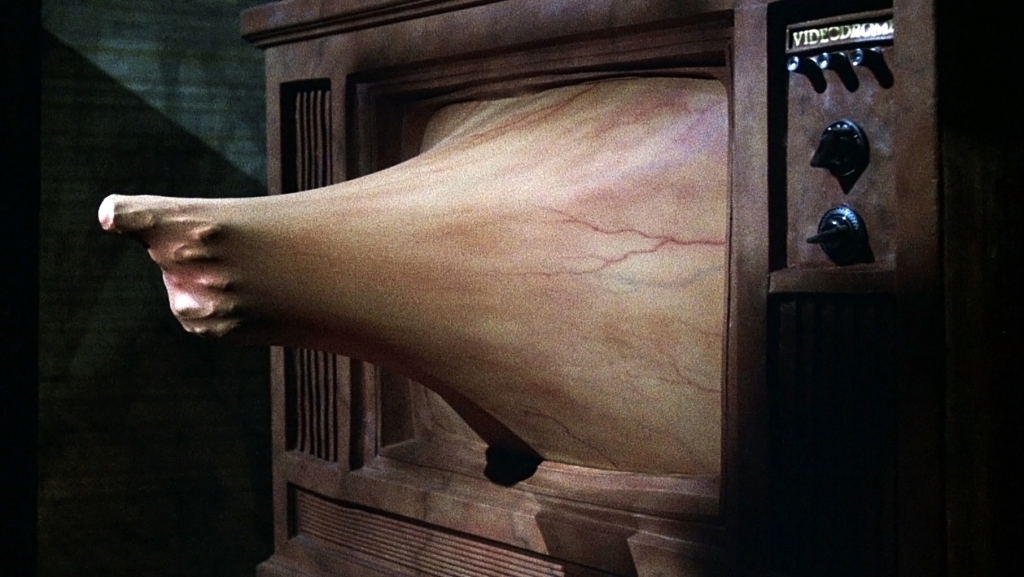

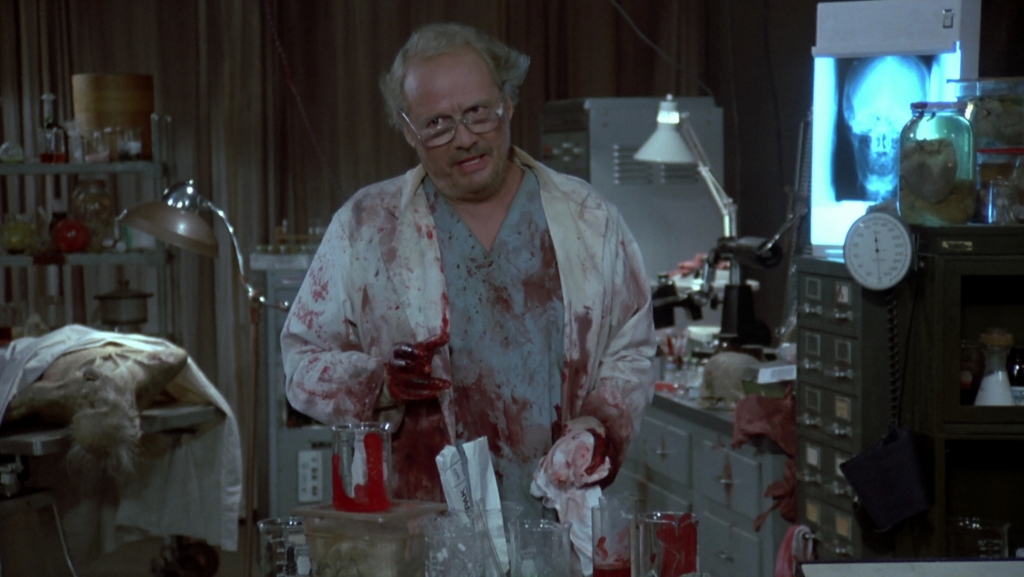

7. Mass Consumption of Misery: Violence as Entertainment in Videodrome (1983)

An Essay by Kourtnea Hogan

Growing up poor in the backwoods, I devoured a variety of media as a way to escape reality. Thankfully, I had a really cool grandma who was obsessed with horror movies and Stephen King, and she helped give me a nudge in the right direction. Soon, horror became my focal point. I craved the visceral violence. If I wasn’t watching horror movies, I was reading horror novels, delving in to true crime, or playing video games like Mortal Kombat.

The internet wasn’t something my family could afford until well into my high school years, so I was trapped in the 90s well after the decade had come to an end. It wasn’t until the mid 2000s that I got to see real gore online.

Sites like rotten.com were notorious places for discovering real life horror when I was growing up. “Oh, you’re reading about Jeffrey Dahmer? You want to see some real shit like that?,” My older cousin leered.

As we flipped through the pictures of mutilated bodies, I felt a weight sink from my throat to my stomach. This wasn’t the beautiful FX work I was fascinated by. This was real human suffering. I was glimpsing into the darkest moments of humanity. I couldn’t help but to think of the families and how horrible I’d feel if I saw someone looking at a crime scene photo of my sister or brother. I had nightmares for weeks. Every time I closed my eyes I would see death.

But I kept ingesting all the horror I could get my hands on, comparing it to the disgusting things I’d seen and judging it on its authenticity.

I became the kind of person who sought out “extreme” horror, wanting to be the one to see the sickest stuff imaginable. And at the time, a lot of it didn’t bother me.

But as I got older, I began to look for what people would come to call “elevated” horror. I wanted a marriage between the gore and the social commentary.

Cronenberg had a huge influence on me, with both The Brood and Scanners among my favorite films. But I was already in college before I finally got ahold of a copy of Videodrome. And I wasn’t prepared for how hard this film was going to hit.

Videodrome felt like a mirror of my life.

I had been sucked into so much violence that I had fallen into a heartless system, just without the body horror.

The older I get, especially with a young son, I worry about media consumption.

I, myself, am against censorship, and I’m not talking about restricting violence in film. But I worry about the easy access to real life violence, and I don’t want my son to grow up in a world where people would rather film murder than try to help. I worry about him seeing the violence of the world regularly regurgitated on Facebook walls and casual tweets.

“You’ve read the fucked up news story; now do you want to see the videos?”

Even now, the line is blurred for me personally.

My son is a part of a generation that has grown up with no memory of school life before Columbine — a generation that has been watching police officers systematically kill black people on the daily news.

How can we separate ourselves from a constant inundation of violence? Where’s the line between the desire to be informed and the morbid fascination with human misery and murder?

Cronenberg felt that the media was exploiting suffering in the 70s and 80s with coverage of serial killers and the violence of the Vietnam War. What would he say about the news today, or even things like the dark web?

It often feels like soon we’ll all be sucked into the TV, one by one, and our pain used as entertainment.

8. Coming Out of the Shadows: Body Positivity in What We Do in the Shadows (Series)

An Essay by Syd Richardson

Editor’s Note: This essay contains plot spoilers for the What We Do in the Shadows television series.What We Do in the Shadows — both in regards to the television series and the show — has been breaking new ground in recent years by bringing back old tropes of vampires. Though we are living in the age of the Twilight series renaissance, and while I don’t personally despise the antics of Bella or Edward, it must be said that Meyer’s books left a decade-long blemish on the good name of the vampire.

Centered around four undead roommates as they try (and often fail) to navigate a hectic, confusing society ruled by humans, the Shadows television show does not shy away from showing the gothic aesthetics and bloodiness that comes with the turf of being a vampire. These bloodsuckers don’t sparkle when in direct sunlight; like vampires of old, they burst into flames.

Even in its revisiting of old vampiric roots, Shadows still manages to break new ground, specifically with regards to sexuality and body diversity. While the vampire has always been a metaphor for realities existing beyond the confines of what society considers normal — ie, straight, cis and heterosexual — it isn’t often that the vampire in media is allowed, freely, to showcase their same-sex attraction. The vampire has historically been more queer coded rather than openly queer. However, in the What we Do in the Shadows television show, every single one of the vampire roommates, at one point, has openly discussed their past or present flings with members of the same sex. In Shadows, all vampires are bisexual (AVAB, baby).

The show also proudly features a handful of people that do not conform to the Hollywood beauty ‘standard’ of being skinny, shapely, and white. This exploration of subtle body positivity, or at least body acceptance, has been exemplified by one character in particular: the vampire’s familiar, Guillermo de la Cruz (Harvey Guillen). As the long suffering, glorified assistant of the 700-year-old vampire Nandor the Relentless (Kayvan Novak), Guillermo’s development from bumbling pseudo-slave to capable, badass vampire hunter, has been nothing short of miraculous.

Tropes of overweight people in media, especially in comedies, have been less than kind to put it very lightly.

At their best, most overweight characters serve as nothing more than physical comedy fodder, or fall into the position of the fat best friend.

And in the first season of Shadows, this seemed to be the route that the writers were going to take — forcing Guillermo into the ‘safe’ role as the overweight, overworked, bumbling sidekick-servant to his cooler-by-association vampire overlords. The first episode of season one falls victim to this especially, even going so far to portray Guillermo as clumsy, an already overused stereotype for fat characters on television.

The semi-problematic nature of Guillermo’s character, however, is remedied as the season progresses, and the vampiric bodies start to pile up. The key moment to Guillermo’s self-actualization, however, comes in the final episode, where he learns of his true lineage. Guillermo learns that he’s the descendant of a vampire hunter, a direct ancestor of Van Helsing.

By season 2, Guillermo is not only turning the ‘overweight sidekick’ trope on its head, he’s absolutely obliterating it — and paving new ground along the way.

The sophomore season of Shadows introduces a new Guillermo, one not bound by pervasive media stereotypes. He openly advocates for himself, and he doesn’t mind driving a couple stakes through some bloodsuckers as he tries to protect his masters from their own idiocy.

And the most striking part is that, at least in outward appearances, there’s no real change in familiar Guillermo versus vampire-hunter Guillermo. There’s no narrative focus or offhand quips on his weight, no cliched montage in which he sheds the pounds so that he can fit into the role of slayer with an ‘acceptable’ new, fit body. No, Guillermo undergoes a metamorphosis into a better version of what he once was, without changing a thing about himself physically.

Guillermo is a fat, queer, grandma sweater-wearing vampire hunter. And as another fat, queer, grandma sweater-wearing media consumer, I appreciate the sentiment that nothing about us physically needs to be altered to become the most-badass version of ourselves.

9. Trust No One: The Authoritarian Danger of Day of the Dead (1985)

An Essay by Jamie Marino

Since Night of the Living Dead, zombie horror movies have (usually cleverly) incorporated some type of social or political commentary within their tales of apocalyptic survival. Somehow, I haven’t become numb and cynical to that, yet.

I remember renting Day of the Dead from the new release shelf at Montage Video, a very horror-centric mom n’ pop video store. I remember that old school Media Home Video tape, and the piss-yellow and mud-grey box. At only ten years old, I may have been a little too young to pick up on all the anti-government and anti-authority sentiment. But I had no problem soaking up all the gore.

For me, Day of the Dead is the goriest, bleakest, and hostile zombie movie I have ever seen. It’s a film that wants to hurt you, and nothing has ever topped it.

Part of what makes it such a beautifully unpleasant and depressing experience is the main character conflict: scientists versus the military.

By this point in George Romero’s canon, returning to a normal social existence is impossible. This is made clear at the very beginning of the movie, as we watch some survivors attempt to contact others in a deserted city. The outcome of that scene is one of the most memorable and iconic zombie sequences ever. And just to hammer that reality home, Dr. Logan later laments that humans are outnumbered by zombies 400,000-to-1.

The scientists are trying desperately to find some type of cure, or vaccine — or at the very least, a way to prolong survival. Their military protectors become more and more impatient with them every day.

Led by the hilariously caustic Captain Rhodes, the soldiers are intimidating, barbaric, sophomoric, overbearing, and more than a little rapey (main character Sarah is sexually menaced several times, and it is even suggested to her at one point that eventually they will abandon their basic morality and humanity and just have their way with her whenever they want). So much for zombies being the most destructive threat in this situation.

The soldiers giggle and guffaw. They don’t act like the last surviving vestiges of mankind, but more like jocks in a locker room. The tough-guy talk is ridiculous, and personally very triggering. They are ignorant bullies, as raw and unfiltered as possible.

I connect this timeless film to our world today for obvious reasons.

Day of the Dead taught me that authority figures can use their powers any way they want. And they can’t be stopped. I got my first glimpse of why I should never trust authority, and I learned early on that our well-being isn’t the main concern of those in positions of power. Rather, it’s all about maintaining that power at all costs.

In Day of the Dead, those entrusted with keeping law and order couldn’t see or appreciate the humanity of those they were sworn to protect. And as it turned out, the one who cared the most in Day of the Dead was the “enemy”. The zombie in the film had more humanity than anyone.

10. Agency and Autonomy: The Feminist Perspective of Swallow (2019)

An Essay by Matthew Currie Holmes

Recently, my 14 year-old daughter and I decided to watch, what we thought was, a quirky little indie thriller called Swallow. What we experienced was nothing short of transcendent.

Swallow tells the story of Hunter (played to perfection by Haley Bennett), a newly pregnant housewife, who seemingly has everything she’s ever wanted. She’s living the idillic life: complete with the perfect husband and the perfect house. Yet something is missing, Hunter is depressed. Turns out having it all is more like a prison sentence than a dream life, especially when her husband (and his family) gaslight her daily.

In an effort to combat her ennui, Hunter turns to swallowing small items that are NOT meant to be swallowed. At first, it’s just for the thrill, something to get her out of her humdrum existence. But as the film progresses and Hunter finds herself increasingly compelled to consume more dangerous objects, it becomes increasingly clear that Hunter must confront the dark secret behind her new obsession.

I don’t want to say too much in case you haven’t seen this beautiful, haunting film. And if you have not seen this masterpiece yet, I urge you to seek it out.

When the movie was finished, I was moved, and challenged… as I am most times when a great movie subverts my expectations.

I was pleasantly surprised. I thought writer/director Carlo Marabella-Davis did an excellent job portraying the horror of gaslighting, and one woman’s struggle for autonomy over her life and her body. I felt like applauding the efforts and saying, “Hear, hear, good job, ol’ chap.”

Then I saw the look on my daughter’s face. Every inkling I had to intellectualize the film’s plot, themes, and purpose went away. Sure, I was moved when I saw the final scene play out in real time. And I could understand what the director was ‘saying’.

But when I looked over and saw my daughter weeping uncontrollably, my understanding of the film took on a whole new meaning.

My daughter is a very bright young womxn. She is a feminist and an activist, and she feels things deeply. This movie knocked her on her ass. She was inconsolable for the better part of an hour. I sat with her, held her tight, and listened while she cried.

At first I thought she was disturbed by the movie. But as we delved deeper into the themes of self-determination and purpose, I discovered she was actually inspired.

I saw the movie though her eyes: the eyes of a 14 year-old trying to find her place in the world. Hearing how she related to Hunter’s plight — how she could understand why Hunter would resort to such drastic measures to gain some sense of control — put the movie in a much more personal space for me.

I couldn’t just intellectualize the film, praising its stunning cinematography and tightly-woven script, I had to understand it.

My gender, race, and privilege prevented me from getting under the surface humanity of what I just watched. But hearing how my daughter felt — as a young womxn who faces micro aggression and pressures almost daily from peers, boyfriends and teachers — gave me considerable pause. I started to cry with her, and the both of us just sat in contemplative silence for the rest of the night.

11. Childhood Scars: Hurt and Healing in It (2017) and It: Chapter Two (2019)

An Essay by Jamie Alvey

There is horror that changes how you view the world in general, and there is horror that changes how you view yourself. For me, It helped me re-contextualize my own past.

One of the most painful parts of adulthood is coming to terms with your traumas in childhood and how those traumas fundamentally changed you. Sometimes it’s difficult to not see yourself as damaged goods, someone who was ruined before they had a chance to truly begin. The memories want to creep in, and you wonder if life will ever be different. The cycle is insidious. And if you push it down and you don’t face it, it will only get worse.

Both It and It: Chapter Two, as well as the original source material, played a keen part in being able to facilitate my own healing. It’s amazing that something that might be commonplace to many, like a movie or a book, can be something revelatory for others.

In It I saw a piece of myself — a piece so intimate that it took years for me to publicly discuss it — reflected plainly and empathetically.

In a bunch of young kids and their adult selves, I saw a reflection of me. It was the ‘me’ as a child and the ‘me’ as an adult who was subsequently working through the muck and the murk of my own condition.

Pennywise may be the obvious villain in the series, but the real horror is the pain of childhood scars that never really heal — and the way Pennywise manipulates this pain to keep his victims paralyzed by fear and self doubt.

But in spite of that trauma, the magic of It is that the members of the Losers Club are never presented as broken or damaged goods.

The films made me realize that — as messy and scarred as I was — there were parts of me that were also good and valuable. The Losers have trauma, yes, and it’s awful, but it’s not unconquerable. And it doesn’t wholly define them. Each one is allowed to exist, with his or her unique strengths and flaws, and still come out on the other side as someone worthy of love and respect.

The films also poignantly explore the idea of love and friendship as a source of healing.

There is great power in people who will hold your hand through your struggles. While they may not fully understand your personal battles, they are there for you when you need them.

Friendship had never been easy for me, and real connection was often a facet of life that evaded me. It took a while to find friends that were a good fit for me, but the wait was worth it. The Losers and their friendship is nothing short of beautiful and one of the loveliest bonds ever portrayed on screen. Their love for one another overcomes all in the end. They have to stand together to hold back the very embodiment of fear itself.

In many ways, It has shaped me in a way that is completely optimistic.

That sounds odd considering the content, but there’s such a reverent beauty to be found in the story. It’s a tale that is ultimately hopeful. It’s a reminder that life is not only tragedy and heartbreak. It’s also about love, hope, and friendship. And no matter how damaged you think you are, you still have inherent worth.

12. Transcendent Love: Breaking Down Boundaries in Let the Right One In (2008)

An Essay by Jess Acev

One of the first movies that came to my mind when I started thinking about this article’s theme was Låt den rätte komma in (Let the Right One In), directed by Tomas Alfredson. This Swedish film is based on the novel by John Ajvide Lindqvist and for me, it remains unforgettable and haunting, because it felt (and still feels) quite personal.

In 2008, when Let the Right One In was released, I had just finished the book and was curious to find out if the film could have the same effect on me, if it could hit me with the same emotions that trapped me as a reader. I was not disappointed. To me, the film adds another dimension to the book. In fact, I would say it works beautifully as an accompanying piece.

Although, the first time I watched Let the Right One In, Sweden was still an undiscovered place, it felt strangely familiar. I knew a lot about the country and its importance to my family. At the same time, it was a faraway land that was beyond my reach.

In the same way, the ideas presented in this film were ones I had begun to explore, but I had not yet fully connected with them in a meaningful way.

Let the Right One In made me confront my own beliefs about loneliness, gender, and love.

Eli and Oskar don’t seem to have more in common than the fact that they are both twelve (more or less as Eli says) and live in the same building. The first time they meet, Eli states that it is not possible for them to be friends. Once they become closer, the initial rejection turns into a question: “Would you still like me if I was not a girl?” Then, when Oskar asks if they could go steady, Eli brings this up again, this time as a statement: “I am not a girl.”

Oskar ignores this, like it is not important at all. What really matters is the idea that they could be together, just the two of them.

I was fascinated by this. Loving someone regardless of who they are, regardless of their gender, was an idea that was not completely strange to me — but I had not yet fully explored it.

The book gets deeper into the fact that Eli is not a girl. But the film shows us that the way Oskar feels about Eli can’t be changed by this discovery. Their bond is so strong that the questions of gender — and the fact that his beloved needs blood to survive — are insignificant.

Like Oskar, I felt lonely as a child.

I had no siblings, and some of my classmates made fun of me because of the way I dressed and the books I read. Finding someone who I could connect with was important, but the chances of that happening seemed limited.

Once I understood that overcoming perceived barriers like gender is possible, the possibilities broadened — and my view of myself and how I want to relate to others became clearer.

Let The Right One In, with its dark beauty, melancholic setting and subtle horror, was the film that truly made the concept that “love is love” hit home for me in a really powerful way.

13. All Monsters are Human: The Violence of Silence in Mon Mon Mon Monsters (2017)

An Essay by The Angry Princess

This wasn’t the film I planned to discuss for this article. However, after watching Mon Mon Mon Monsters, I felt compelled to talk about it — especially in light of current events.

Maybe the reason this film hit so hard for me was precisely because of when I watched it — in the midst of a renewed battle against systemic racism and injustice, in a nation being torn apart by a culture of ‘us’ vs ‘them’. It’s a time when we’re talking about the dangerous consequences of inaction and silence in the face of oppression and cruelty; a time that makes us re-evaluate what it means to be a “good guy” and to question our willingness to fight for what’s right, even when it’s not comfortable or beneficial to do so.

This film, about a group of Japanese teenagers who kidnap and torture a young female monster, is really about how we demonize and persecute those we consider to be ‘other’. It’s about how we justify unspeakable horrors against those we consider less than ourselves. And it’s about the cycle of abuse, in which pain begets more pain — the way in which victims can so easily (and willingly) become victimizers.

Mon Mon Mon Monsters is a tense, heartbreaking, and horrific film about the monster that resides within all of us.

Unjustly accused of stealing money, the shy and friendless Lin Shu-wei is assigned to do community service alongside the bullies from class, which consists of leader Tuan Ren-hao, his girlfriend Wu Si-hua, Liao Kuo-feng, and Yeh Wei Chu. In order to gain the acceptance he’s never had, he begins to take part in the group’s petty misdeeds. While out causing mischief one night, they stumble upon a pair of flesh-eating female ghouls and capture the younger one of them. They begin a sadistic game, which ultimately leads to disastrous consequences.

The toxic and hateful Ren-hao takes great pleasure in having the monster as a captive. Because it’s not a human, he states they can do anything they want to it — free from consequences or guilt.

Shu-wei does not share his enthusiasm, instead sympathizing with the ghoul and trying to comfort her. However, while Shun-wei does not instigate, or even sanction, the increasingly savage violence the gang perpetuates against the helpless creature, he also makes no attempts to stop it — concerned more for his own safety than her well-being.

When it becomes apparent that the monster is dying from starvation, and in need of human blood to survive, Shun-wei agrees to let the group take his blood to feed her. For this act of ‘sacrifice’, he convinces himself that he’s the hero of the story.

In fact, writer/director Giddens Ko brilliantly exploits the audience’s tendency to empathize with Shun-wei, a victim of abuse and neglect himself.

We want him to be the good guy, to triumph over the bullies and reflect our own humanity.

But Ko subverts these expectations time and time again, reminding us that Shun-wei is no hero, as he stands by silently while the ghoul is chained to a pillar; repeatedly tortured, screaming out in constant anguish.

Later, Si-hua reinforces this when she calls him out for his hypocrisy and mocks him for holding himself up as “the good guy” even though he lacked the courage to really do what’s right and free the monster. Shu-wei then shifts from bullied victim to oppressor, taking out his anger on an innocent, autistic convenience store clerk, wrecking the store and stealing its money.

This tendency to attack someone weaker whenever a character feels emasculated or shamed is a common theme throughout the film.

When Ren-hao is humiliated by his teacher in front of his friends and a classmates’ parents, he returns to brutalize the ghoul more viciously than ever before. He then seeks revenge against the teacher that wronged him in the most extreme and cruel way imaginable, as his classmates look on — not in horror, but in sick fascination, while laughing and filming her agonizing death on their smartphones. It’s a scathing commentary on a contemporary youth culture defined by apathetic indifference to the suffering of others and a grievous lack of empathy.

In the end, Shun-wei tries to do the right thing, but only in the interest of self preservation.

Despite the unquestionable role he has played in the younger monster’s prolonged torment, he believes he should be absolved of all his sins and given a pass because, as he states when pleading his case to the older ghoul who shows up hell bent on revenge, “I’m the good guy.”

It all culminates in a devastating but poetic ending that effectively hammers the message of the film home; a commanding gut punch you won’t see coming.

Mon Mon Mon Monsters can easily be enjoyed by horror fans purely for its entertainment value. It’s an ultra gory — and surprisingly funny — bit of visceral filmmaking. It’s also incredibly mean-spirited, which is entirely the point. Because, as fun as this film is, Giddens Ko has some very important things to say about man’s capacity for cruelty and the monsters we all keep chained up inside ourselves. And if you refuse to listen, he won’t let you off the hook by claiming, “But I’m the good guy.”

…

Follow Us!